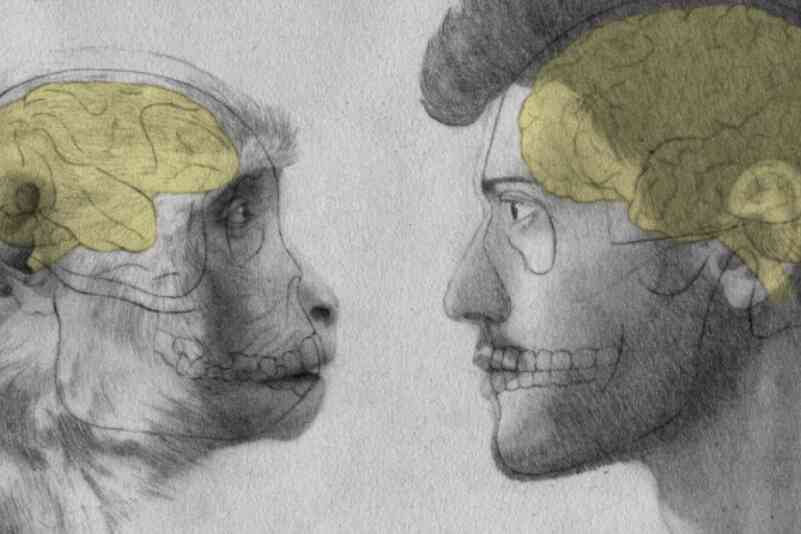

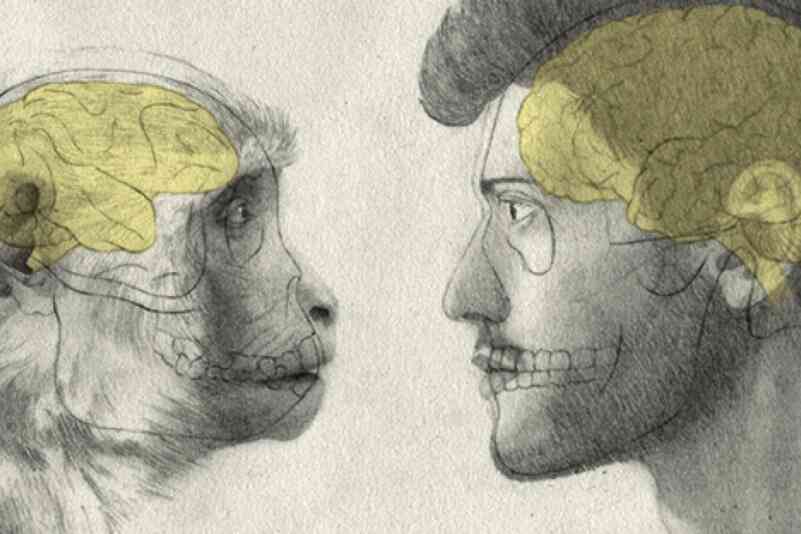

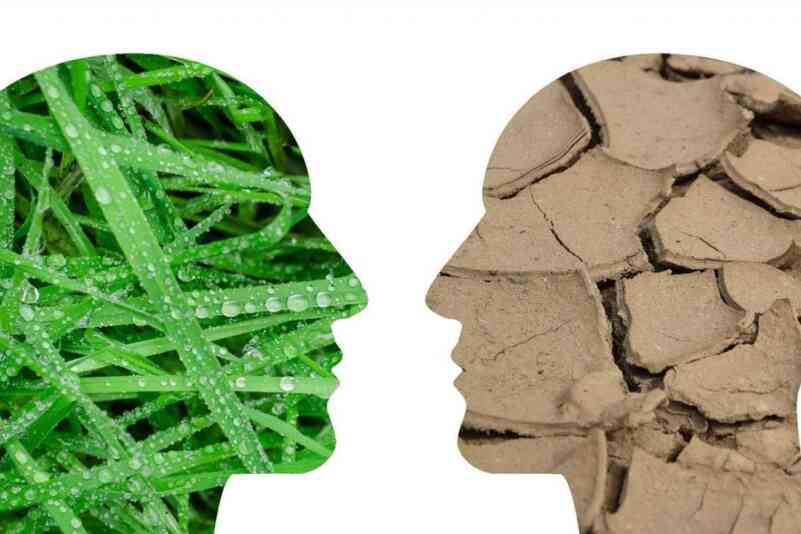

Empirical data suggest more men are dying from COVID-19 than women [1]. A conclusive explanation is still lacking. It may be down to biological reasons, but differences in lifestyle and behavior resulting from traditional gender norms are also likely to play a role. Men, for example, are less likely to take hygiene and protective measures seriously [2]. That behavior is displayed in the fact that men, out of fear of looking weak, are more reluctant towards wearing face masks than women [3]. These findings indicate that gender norms and especially traditional ideals of masculinity play a crucial role in shaping health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

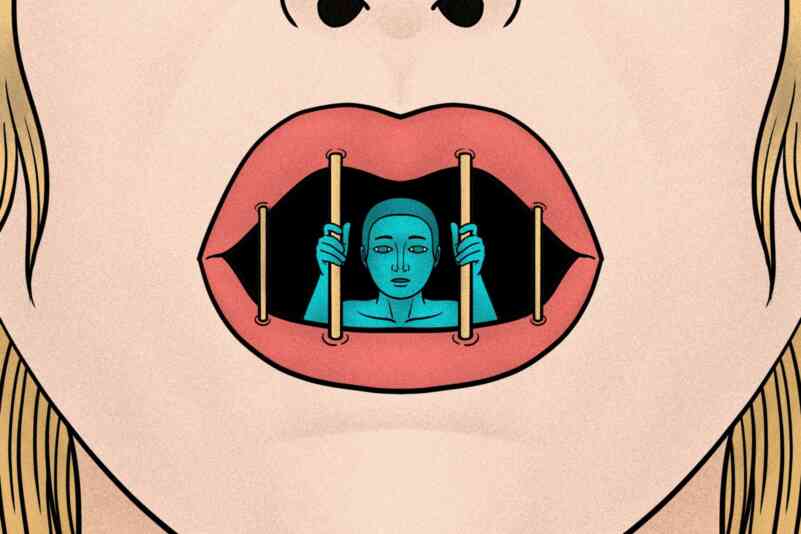

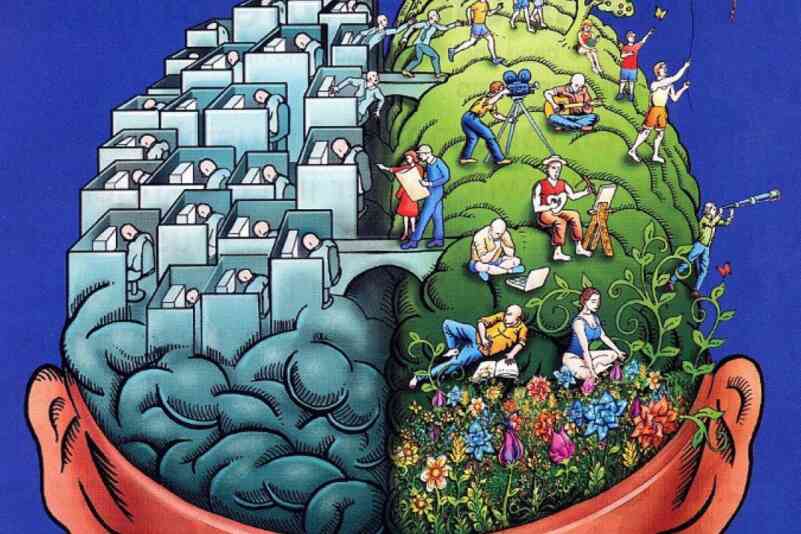

But why are some men so afraid of «looking weak» that they would rather risk dying from the virus than wearing a mask? In search of an answer to this question one soon comes across the term «toxic masculinity».

The meaning of toxic masculinity

The term has become popular through the #MeToo-movement and is often used to explain or blame aggressive, dominant behavior of heterosexual men. While some value its explanatory power and acknowledge toxic masculinity as a real but solvable problem, others dismiss the concept, misinterpreting it as a criticism of being male [4]. A closer look, however, quickly reveals the true meaning of the concept. Toxic masculinity does not assume masculinity or being male to be toxic. Rather, «toxic» qualifies the term «masculinity». That is, it emphasizes that certain traits of masculinity can be harmful – for men themselves and for others.

Generally speaking, toxic masculinity refers to a type of masculinity «that is threatened by anything associated with femininity (whether that is pink yogurt or emotions)» [5]. Toxic masculinity results from the fear of not being «masculine enough» and includes behaviors and beliefs such as suppressing emotions or masking distress [6].

The opposition to anything feminine can be the result of being socialized to conform to traditional ideals of masculinity [7]. It is the consequence of telling boys things like «don’t be a girl» or «man up», and accepting violence and aggressive behavior because «boys will be boys». This social expectation to be strong and dominant in order to be «a real man» leaves (some) men with a very fragile ego, preventing them from showing weakness or vulnerability [6]. When social, political, or economic changes (or, as we shall see, pandemics) challenge traditional ideals of masculinity or somehow prevent a man from living up to societal expectations, some men react with aggression to their insecurities to maintain an appearance of toughness and use violence as an indicator of power [6] [7].

COVID-19 and toxic masculinity

According to public health experts, wearing a mask is one of the most effective measures people can take to slow the spread of COVID-19 [8], thereby protecting themselves and others. Yet, not everyone is willing to wear a mask: men seem to be more reluctant to mask-wearing than women [9]. Based on an original survey, Dan Cassino and Yasemin Besen-Cassino found that among men, «those who say that their gender identity is ‘very important’ are less likely to support mask requirements than those who say that their gender identity is ‘not important’» [10]. Other research reveals that an expressed desire to appear «tough» helps predict who will refuse masks [11].

These findings support the view that the failure to wear a mask has nothing to do with being male but with men’s relation to their masculinity. If for some reason men feel pressured to appear «masculine», they are less willing to wear a mask.

Peter Glick, a professor of social sciences at Lawrence University, whose research focuses on understanding and overcoming biases and stereotyping, explains the aversion towards masks with a core principle of masculinity: «show no weakness» [12]. Thus, by sending the underlying message «I’m afraid of catching COVID-19» which is equal to appearing weak, masks seemingly emasculate.

In this sense, it can be argued that the pandemic threatens traditional ideals of masculinity and therefore provokes a toxic form of masculinity. Hence, the pandemic is shining a spotlight on toxic masculinity and, tragically, its negative consequences for men themselves and others.

Two prime examples of toxic masculinity

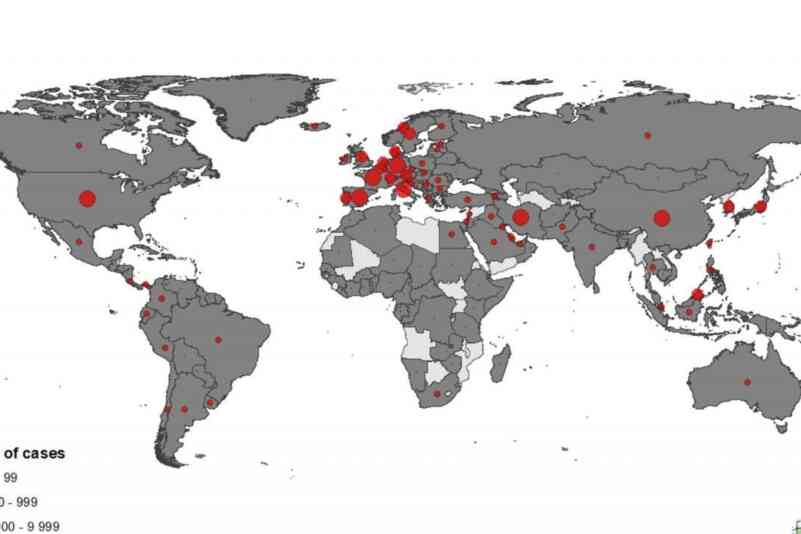

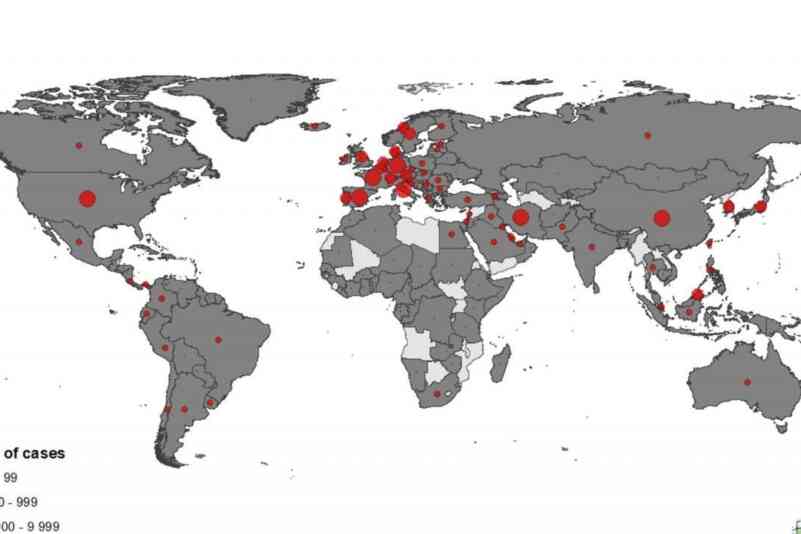

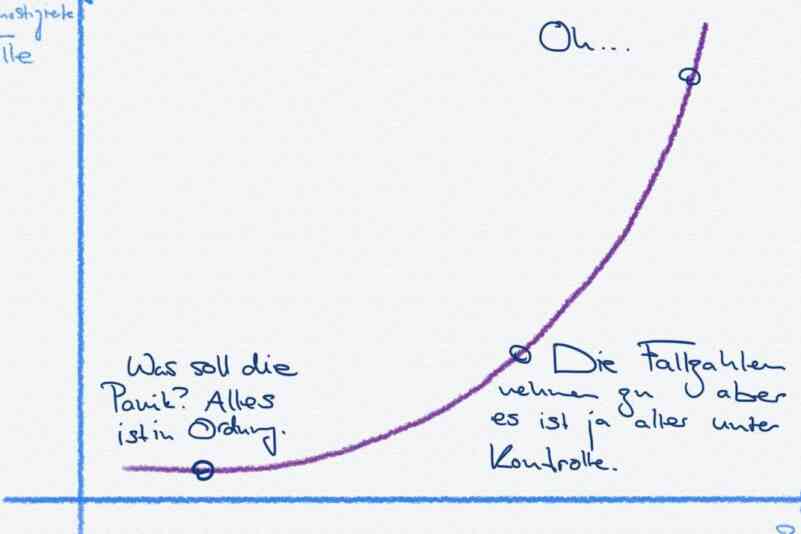

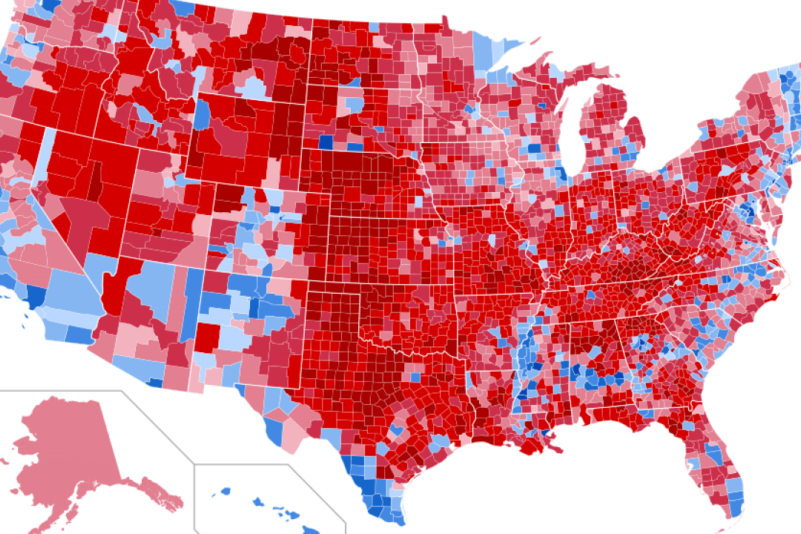

The dangerous effects of toxic masculinity are evident not only in individual men refusing to put on a mask but also in the responses to the pandemic by political leaders like Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro or former U.S. President Donald Trump. Both, Trump and Bolsonaro, are clear examples of men who cling to toxic forms of masculinity. They rely on sexism, misogyny, and violence to fight anything that seemingly threatens their dominance and their egos [13].

As if this wielding of toxic masculinity as a form of political showmanship was not bad enough in itself, under the current pandemic it has become a deadly threat to the two countries they preside(d) over: Brazil and the United States record among the highest numbers of infections and death tallies worldwide [14].

At the beginning of the pandemic, Trump and Bolsonaro both downplayed the danger of COVID-19 and refused to wear a mask or obey social distancing rules because it would «look weak». Bolsonaro, for example, described the pandemic as a flu and said that Brazil had to «stop being a country of sissies» [15]. Once it was no longer tenable to ignore the severity of the pandemic, both leaders have pivoted, presenting themselves as hyper-masculine war heroes concerned with protecting their countries from an «invisible enemy» [16]. By positioning the virus as an enemy, they shifted attention away from their poor handling of the pandemic and instead fostered the narrative of them protecting the nation.

It is tempting to laugh at the sheer absurdity of Trump’s and Bolsonaro’s statements. But the reality is that their fear of showing vulnerability highlights how toxic masculinity has impeded the efforts of public health officials to contain the spread of COVID-19 and has led to an ever-rising body count. Thus, the question, if female leaders are better equipped to handle the pandemic, seems justified.

Female leaders as the solution?

Many media outlets, for example the Guardian, have reported that countries with a female leader are managing the pandemic better than those led by males [17]. The conclusion that female leaders are better leaders in times of a global health crisis thus seems straight forward. However, it is misguided.

To see why, we have to recapitulate the definition of toxic masculinity. It does not state that being male is toxic, rather it means that certain traits of traditional ideals of masculinity can become toxic when men feel that their masculinity is somehow questioned. So, the problem of the poor handling of the pandemic by leaders such as Trump or Bolsonaro is not down to them being male but is rooted in the fact that behind the surface they have fragile egos and are afraid to show vulnerability.

A study by Andrea Aldrich and Nicholas Lotito supports this view. They explored the relationship between the sex of political leaders and the timing of imposing protective measures and found no statistical evidence that supported the claims made in the media [18].

So, we do not necessarily need female leaders, but leaders who have a relaxed attitude towards their gender identity. We do not need political leaders who, in an effort to appear «strong», reject any «feminine» behaviors, but leaders who allow public health experts to lead policy and themselves to display empathy and solidarity.

Articles on the topic

14. Januar 2026 | Maurice Lanz

Die Demokratie steht heute an einem Scheideweg. Während sich Gesellschaft, Technologie und Kommunikation rasant weiterentwickeln, wirken…

7. November 2025 | Lorjen Doehler

This opinion piece argues that much of the West’s energy transition can no longer count on politics. And, crucially, it no longer has to.

24. Oktober 2025 | Xulia Maillot Rodriguez

Rare earth elements, so hidden and so critical, seem to be quietly ruling our world. Add to that a market strained by geopolitical tensions, a…

9. September 2025 | Marcus Yong

In a world increasingly dominated by short-form content, science needs a new marketing strategy. Can scientific short-form content be both fun and…

14. August 2025 | Jelena Magnin

If you could shrink yourself down to the size of a bacterium and travel inside your own body, you’d discover an entire world teeming with life.…

8. August 2025 | Markus C. Wagner

Wie sichern wir unsere Demokratie und Informationsfreiheit im digitalen Zeitalter? Das Schweizer Netzwerk bietet eine zukunftssichere Antwort: Eine…

19. Juni 2025 | Teseo La Marca

In Neve Shalom/Wahat as-Salam leben jüdische und palästinensische Israelis eng zusammen. Was die israelische Gesellschaft von ihnen lernen kann.

12. Juni 2025 | Reja Wyss

Spätestens seit der Corona-Pandemie erfährt der Begriff «Krise» neue Aktualität. Doch sind wir für die Krisen der Zukunft gewappnet? Die…

4. Juni 2025 | Vilhelmiina Haavisto

For every 10 apartments built in Switzerland every year, one is torn down. Construction and demolition contribute 1/3 of Switzerland’s carbon…

25. Mai 2025 | Salomé Perret

Wie nutzen Pflanzen ihr unterirdisches Wurzelnetzwerk, um zu kommunizieren? Und warum sind Regenwürmer und Mikroorganismen so unersetzlich? Boden ist…

16. April 2025 | Evamaria Fuchs

Schon vor über 2000 Jahren haben es die Römer geschafft, sich durch diplomatisches Geschick kritische Rohstoffe und gut gehütete Betriebsgeheimnisse…

7. April 2025 |

Etwa jeder zweite Mensch weltweit ist bilingual. Bilingualität zeichnet sich durch die tägliche Nutzung einer zweiten Sprache aus. Sprichst du selbst…

20. März 2025 | Katharina Wiegmann

Streiken, kleben, diskutieren. Was bringt das wirklich? Ein Protestforscher bringt Licht ins Dunkel – und erklärt, warum schon eine Umarmung…

7. März 2025 | Sarah Evison

Velofahren boomt – dank Covid-Pandemie und zunehmendem Umweltbewusstsein. Die Velostadt erscheint als zukunftsweisendes Mobilitätskonzept in der…

4. Februar 2025 | Jose Luis Ocana Pujol

Solar cells convert only a small fraction of sunlight into electricity — so how have they become the world’s fastest-growing energy technology?

30. Januar 2025 | Kaspar Meuli

Am 3. Dezember fand an der Universität Bern eine Podiumsdiskussion zum Verhältnis von Wissenschaft und Politik statt. Fazit: Ob sie wollen oder…

23. Januar 2025 | Elisabeth Abs

Wie wir uns ernähren, ist nicht nur wichtig für unsere Gesundheit, sondern auch für die Gesundheit unseres Planeten. Ein von Experten entwickelter…

17. Januar 2025 | Lorjen Doehler

Adam Smith, hailed as the father of modern economics, is often inseparable from the idea of the “invisible hand”. The invisible hand is widely…

9. Januar 2025 | Dirk Walbrühl

Eine Initiative aus Naturschutzorganisationen, Unternehmen und Forscher:innen bastelt an einem Warnsystem für die Natur. Ausgerechnet Geier spielen…

21. Dezember 2024 | Lea Bächlin

Wie könnte die Landwirtschaft in Zukunft mehr als 8 Milliarden Menschen ernähren, ohne der Umwelt zu schaden?

19. Dezember 2024 | Matilda Jordanova-Duda

Wie KI hilft Wartezeiten, riskante Überquerungen bei Rot und unnötige Autostopps signifikant zu reduzieren: Die smarte Wiener Ampel erkennt von…

12. Dezember 2024 | Dea Müller

Is everything lost in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria? If it was, I wouldn’t be writing this. Let’s explore a lesser-known solution…

5. Dezember 2024 | Maximilian Spitz

Die Schweiz wächst schnell und es wird viel gebaut. In welche Richtung sich die Schweizer Baulandschaft entwickelt, ist noch ungewiss. Gewisse…

28. November 2024 | Stefano Hauswirth

Energy production will need to be expanded. Nuclear energy, instead of being phased out as is currently planned, should instead be embraced,…

16. November 2024 | Dea Müller , Benedikt Schmidt , Dominik Scherrer

Sollte Wissenschaft die Politik gestalten? Kann sie sich dem Politischen überhaupt entziehen?

9. November 2024 | Jonas Füglistaler

Die Arbeitsgruppe "Verantwortungsvolle Tierversuche” von Reatch lehnt die Initiative «Ja zur tierversuchsfreien Zukunft» ab. In den Faktenblättern…

7. November 2024 | Rahel Schmidt , Jan Isler

Am Reatch Ideenwettbewerb 2022 gewonnen und nun vom Franxini Innovation Hub unterstützt: Rahel Schmidt und ihr Team handeln

31. Oktober 2024 | Florian Berlinger

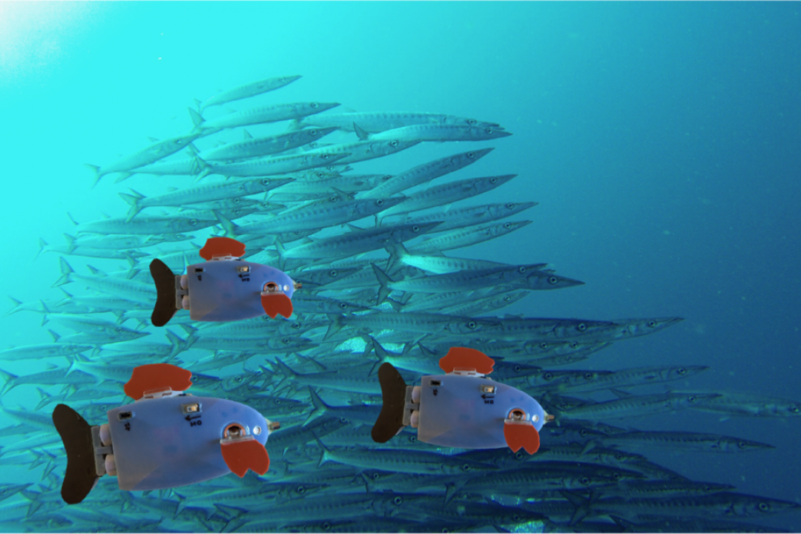

While observing my underwater swarm robots one might think that the differences between them and real fish are decreasing rapidly. But there is still…

24. Oktober 2024 | Jankó Weibel , Summer Academy 2023

“This film will change millions of lives around the world” - this self-description of the documentary “Below the Belt” catches the eye - and sets…

17. Oktober 2024 | Alina Hunkeler , Gian Giacomo Ruschetti

Der Übertritt in den Ruhestand ist für ältere Menschen zunehmend mit Unsicherheiten verbunden. Einsamkeit im Alter und Altersarmut sind…

10. Oktober 2024 | Elisabeth Abs

Macht die Schweiz genug, um das 1.5-Grad-Ziel des Pariser Klimaabkommens zu erfüllen und die Klimakatastrophe abzuwenden? Nein, findet die Gruppe…

3. Oktober 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Viele Schweizerinnen und Schweizer zeigen sich empört über Tierversuche, wollen aber trotzdem von den daraus gewonnen Erkenntnissen profitieren.…

22. September 2024 | Anton Schreiber

Was beeinflusst, wieso wir manche Musik mögen und manche nicht?

20. September 2024 | Chantal Adelmann

Nutzbringende Leistungen aus der Natur werden anhand von Ökosystemleistungen quantifiziert, um Umweltverschmutzung oder die Zerstörung von…

18. September 2024 | Thomas Friemel , Nico Pfiffner

Mittlerweile wissen die meisten, dass wir mit jedem Like bei Instagram, jeder Sucheingabe bei Google oder jedem Tracking über eine Fitness-App…

17. September 2024 | Henry Broadbent

Biodiversity, the diversity of living organisms, plays an important role in the evolution and survival of species. However, human activity is causing…

25. August 2024 | Anna Hahn

Was hat Gesundheit mit Nachhaltigkeit zu tun? Was kann das Gesundheitswesen tun, um Ressourcen verantwortungsvoll einzusetzen, ohne das Recht auf…

21. August 2024 | Sabrina Burkhard

Hitzewellen werden bei fortschreitendem Klimawandel häufiger, intensiver und länger. Die Hitze führt vor allem bei der älteren Bevölkerung zu…

20. August 2024 | Benedikt Schmidt , Servan Luciano Grüninger , Anna Funk

Die Gaza-Proteste an Schweizer Universitäten haben das Verhältnis von Wissenschaft und Politik erneut in den Fokus gerückt. Es ist nicht das erste…

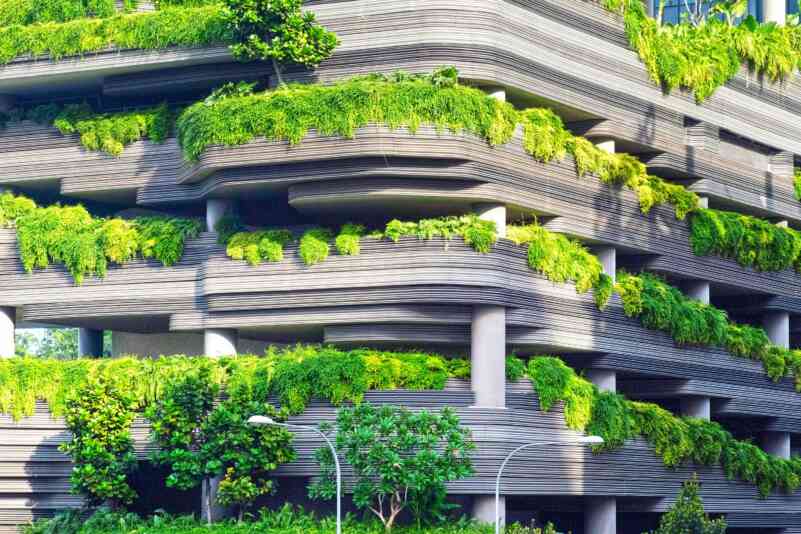

14. Juli 2024 | Zoubeir Saraw , Marion Langlet

How to make constructions more environmentally friendly?

11. Juli 2024 | Karin Kook , Tomas Marik

Ein Blick in die Zukunft der städtischen grünen Räume: Dr. Karin Kook teilt ihre Vision für die Freizeitgärten in Basel mit Tomas Marik und…

28. Juni 2024 | Jasmine Kofmel

With a growing number of teenage asylum seekers arriving in Switzerland, it is crucial to address their challenges and vulnerabilities, and to…

24. Juni 2024 | Vilhelmiina Haavisto

Switzerland is a world-leader in recycling electronic waste, but in the wake of the climate crisis, reducing consumption is more important than ever.…

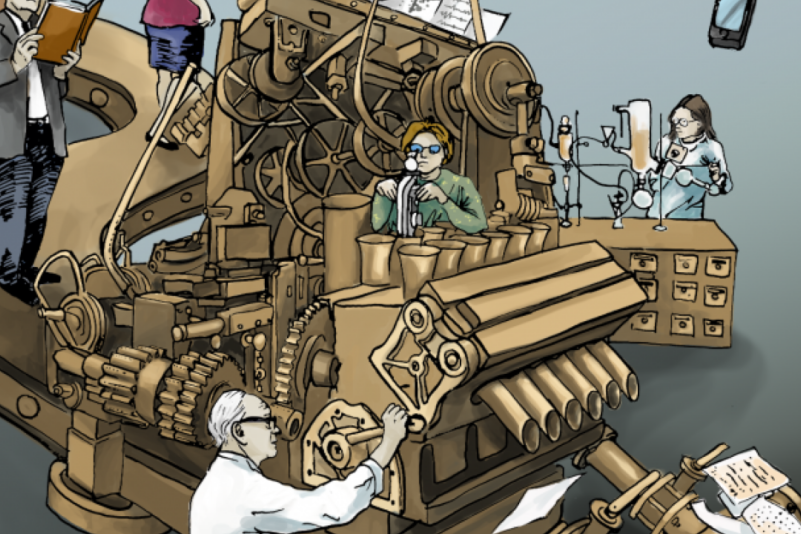

20. Juni 2024 | Florian Gasser , Mauro Gotsch

Trotz einer Demokratisierung der Massenkommunikation ist die öffentliche Wahrnehmung der Forschung durch private Organisationen gesteuert, welche den…

13. Juni 2024 | Stefano Hauswirth

Energy production will need to be expanded. Nuclear energy, instead of being phased out as is currently planned, should instead be embraced,…

10. Juni 2024 | Jan Lazarevski

Preisgekrönt stehen sie mitten im Mailänder Stadtzentrum. Insgesamt 116 und 84 Meter hoch, zwei Türme aus Metall und Glas – übersät von unzähligen…

7. Juni 2024 | Yarik Kuznetsov

In der Schweiz, einem Land, das für seine Innovation bekannt ist [1], stehen wir vor einer Reihe von globalen Herausforderungen. Diese betreffen die…

6. Juni 2024 | Ronald Hyams

Digital transformation, artificial intelligence, and social media can be positive factors in Swiss and global society. However, the resulting…

5. Juni 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Olga Baranova

Die Uni-Proteste dominieren zurzeit die Berichterstattung über die öffentliche Debatte zum Krieg im Nahen Osten. Doch das berechtigte Interesse…

30. Mai 2024 | Anna Knörr

Wissenschaftler:innen und Menschen aus Politik und Verwaltung sind keine zwei verschiedene Spezies. Doch was einem nicht oft im Alltag begegnet, das…

27. Mai 2024 | Benedikt Schmidt , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Das Zusammenspiel von Wissenschaft und Politik ist nötig, um gesellschaftliche Herausforderungen anzugehen. Es ist jedoch kein Freipass dafür, die…

21. Mai 2024 | Sebastian Bolli , Noel Rhyner

We argue that Switzerland needs to establish a largely independent electricity supply and abolish the path of hardly controllable dependency.

20. Mai 2024 | Xulia Maillot Rodriguez

We've always told you that practicing sport is good for your health. And that if you want to stay in tip-top shape, it's best to look after your…

20. Mai 2024 | Joel Michel

Ethikkommissionen sind fest im politischen, medizinischen und wissenschaftlichen System der Schweiz verankert. Doch was sind und machen…

15. Mai 2024 | Michaela Egli , Benedikt Schmidt , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die Verteidiger und Kritiker aktivistischer Wissenschaft reden aneinander vorbei, statt einander ernst zu nehmen. Das bringt wenig Einsicht und viel…

13. Mai 2024 | Reatch! Research. Think. Change.

Die gegenwärtige Polarisierung im Umgang mit Wissenschaft in Politik und Öffentlichkeit sorgt dafür, dass Wissenschaft an widersprüchlichen…

8. Mai 2024 | Tobias Hauser

Unsere Demokratie kann auf eine reiche Geschichte zurückblicken und einen Grossteil des gesellschaftlichen Fortschritts als ihren Erfolg verbuchen.…

6. Mai 2024 | Guido Baldi

Europas Wirtschaft wird oft übertrieben stark schlecht geredet. Europa befindet sich wirtschaftlich nicht im Niedergang.

2. Mai 2024 | Tara Niamh Tošić

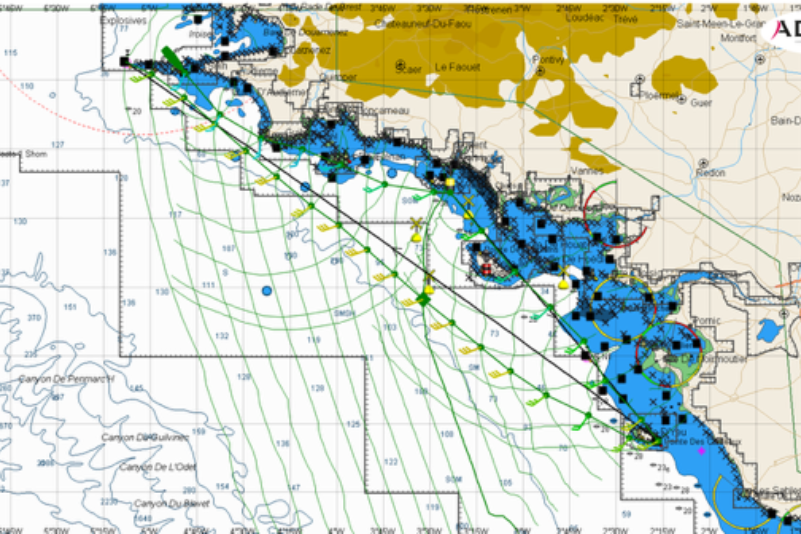

Today we meet Felix Oberle, professional sailor and mechanical engineer. This young sailor from Aarau will tell us about sailing route optimization…

29. April 2024 | Kolja Rath

Large language models (or LLMs), like Google’s Bard, or OpenAI’s ChatGPT seem to have taken over the internet and chances are, you might have tried…

18. April 2024 | Markus Schärli

Noch sind nicht-menschliche Wesen vom Rechtssystem unserer Gesellschaft ausgeschlossen. Als Nicht-Personen können sie kein Gericht anrufen. Es ist…

9. April 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Gelangen wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse in die Politik, dienen sie Zielen, die nicht jene der Wissenschaft sind. Das Beispiel der Statistik zeigt,…

24. März 2024 | Sean Oppliger , Delia Kwakye

In dieser Podcast-Episode tauchen wir tief in das Phänomen des Flow-Zustands ein; jenes begehrte Gefühl des vollkommenen Aufgehens in einer…

21. März 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die Schweiz gehöre längst zur wissenschaftlichen Elite, doch im Geist sei sie ein Volk von Bäuerinnen und Bauern geblieben, schreibt Biostatistiker…

12. März 2024 | Maud Steinbach

Das Gehirn zu verstehen ist ein Traum der Menschheit. Doch trotz intensiver Forschung bleiben die Erkenntnisse rudimentär. Liegt dies an einem Mangel…

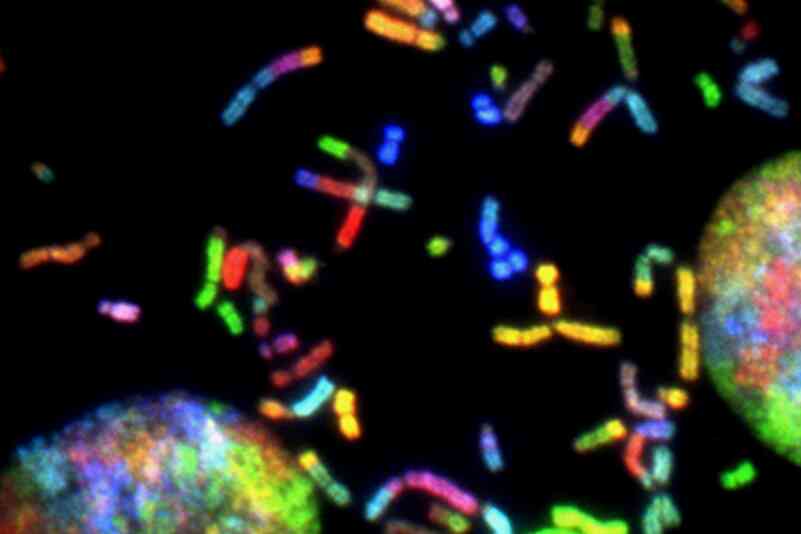

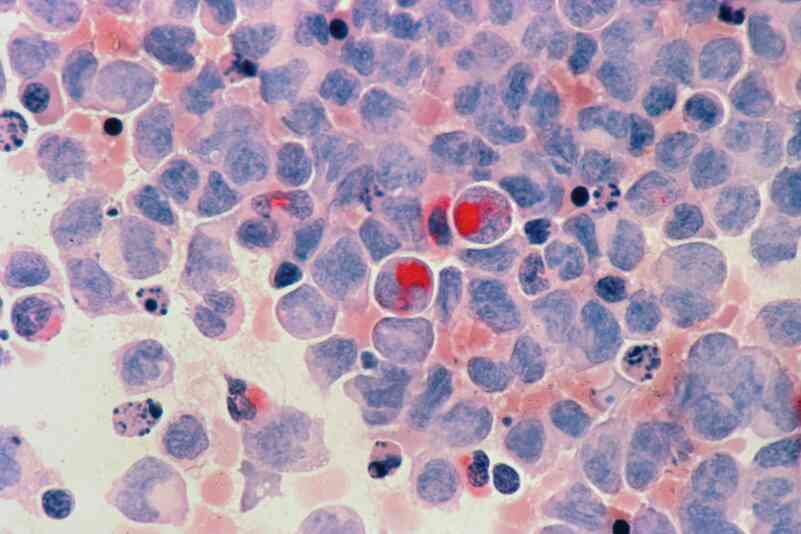

10. März 2024 | Jennifer Steiner

Krebs – eine Krankheit mit der die Mehrheit von uns bereits in Kontakt gekommen ist. Da es verschiedenen Arten von Krebs gibt, ist die…

7. März 2024 | Mykola Makhortykh , Aleksandra Urman , Maryna Sydorova , Hannah Schoch

Dass KI-basierte Systeme (zum Beispiel Suchmachinen wie Google oder Chat-GPT) einen grossen Einfluss haben, ist unterdessen bekannt. Wie dieser…

29. Februar 2024 | Elisabeth Abs

In der Schweiz sind mehr als 500.000 Menschen von einer seltenen Krankheit betroffen. Welche Hürden müssen diese Patient*innen nehmen und wie kann…

21. Februar 2024 | Elisabeth Abs

Am 4.12.2023 lud das Reatch Blog Team zu einem Netzwerkanlass an der Universität Bern ein. Gästin des Abends war Katrin Zöfel,…

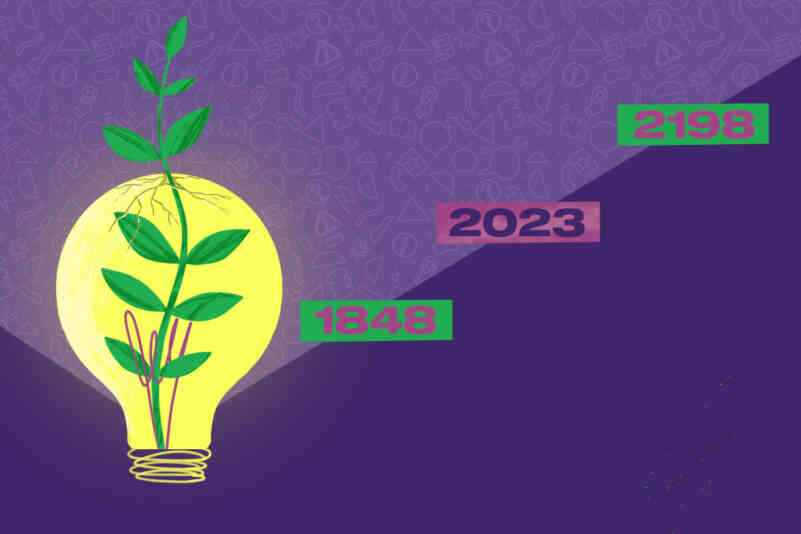

15. Februar 2024 | Reatch! Research. Think. Change.

Die Schweiz wird 175 Jahre alt. Dieses Jubiläum nutzt die Ideenschmiede Reatch und ruft zum Ideenwettbewerb auf. Wie schon 1848 soll der Pioniergeist…

1. Februar 2024 | Reatch! Research. Think. Change.

Reatch lehnt die vom Bundesrat vorgeschlagene Senkung der Radio- und Fernsehabgabe ab. Bevor über den Preis verhandelt wird, braucht es strategische…

30. Januar 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Der Staat gibt Milliarden aus für die Forschung. Wieso es sich lohnt, damit auch jene Dinge zu erforschen, die fragwürdig oder skurril erscheinen…

30. Januar 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Der Journalist Rico Bandle erzählt im Interview, warum es anmassend ist, wenn er die Qualität von Forschung kritisiert, und warum sich Forschende…

30. Januar 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Madeleine Pape is a sociologist of gender at the University of Lausanne. In the interview, she discusses sex as a policy object, the public…

28. Januar 2024 | Pauline Oeuvray

Qu’est-ce qu’ont en commun la permaculture robotique et la prise en charge des victimes de violences sexuelles? Ces deux idées ont été primées par le…

26. Januar 2024 | Sonja Leyvraz

Mobility systems are key to our lives - how must we build them to reflect core values such as equity, sustainability, and accessibility? What role…

23. Januar 2024 | Rahel Schmidt , Leon Guggenheim , Jan Isler , Janina Inauen , Fabienne Odermatt

Das Franxini Innovation Hub Projekt «Opfer sexualisierter Gewalt im Fokus» hat zum Ziel, die Betreuung von Opfern sexualisierter Gewalt in der…

19. Januar 2024 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die Komplementärmedizin soll mit dem Placebo-Effekt Werbung machen, um ihr Image zu verbessern, meint Sabine Kuster. Doch oftmals ist der…

11. Januar 2024 | Selina Wegmüller , Eva Maria Hodel

Wie kann die Zusammenarbeit von Politik und Wissenschaften bei der Vorbereitung und Reaktion auf Pandemien am zielführendsten gestaltet werden?

28. Dezember 2023 | Anton Schreiber

Ständig bewerten wir Musik. Doch das ist eigentlich gar nicht so einfach, wie der Vergleich zweier unterschiedlicher Musikstile zeigt.

22. Dezember 2023 | Aleksandar Žužul , Alena Luna Weibel

Daten und Statistiken beeinflussen nicht nur unsere täglichen Entscheidungen, sondern spielen auch bei gesellschaftspolitischen Debatten eine…

14. Dezember 2023 | Maren Anheuser , Florentina Vlasaku

Statistische Analysen sind das Rückgrat jeder Datenauswertung: Sie enthüllen verborgene Muster und schaffen neue Erkenntnisse. Doch welche Risiken…

8. Dezember 2023 | Lisa Jödicke

Die Dateninterpretation ist ein wichtiger Bestandteil der Statistik. Lisa Jödicke beschreibt am Beispiel des «Hungry Judge Effect», was es dabei zu…

4. Dezember 2023 | Nicolas Zahn

Popkultur ist ein mächtiges aber wenig genutztes Werkzeug in der Vermittlung von wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen. Ein Beispiel findet sich in einer…

30. November 2023 | Laura Betschka , Anna Funk

Jede statistische Analyse braucht Daten. Doch wie werden Daten überhaupt gesammelt? Und wie wird sichergestellt, dass sie verlässlich und…

23. November 2023 | Ilona Gretener , Julia Zingerle , Selina Scherrer

Die Menge an Daten wächst exponentiell. Auch der Staat erhebt Mengen an Daten, doch nur ein kleiner Teil davon ist für die Öffentlichkeit zugänglich.…

16. November 2023 | Nicole Hasler , Jan Müller , Fabian Schneider

Jede statistische Analyse braucht Daten. Doch wie werden Daten überhaupt gesammelt? Und wie wird sichergestellt, dass sie verlässlich und…

26. Oktober 2023 | Céline Jenni

Das Bild von Sherlock Holmes auf der Suche nach verdächtigen Hinweisen wird wohl bald von einem virtuellen Ermittler überdeckt. Künstliche…

10. Oktober 2023 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Vor 175 Jahren wurde die moderne Schweiz geschaffen – geeint durch eine Verfassung, aber geteilt durch Sprache und Religion. Das Entstehen einer…

24. September 2023 | Reatch! Research. Think. Change.

Ohne nachhaltige Investitionen in Forschung, Bildung und Innovation (BFI) droht die Schweiz den Anschluss zu verlieren. Aus diesem Grund sollte der…

22. September 2023 | Pascal Kägi

Are you working in a green job? After reading this article, you will know what a green job is and how the concept of green jobs can help us green the…

19. September 2023 | Laurence Kissling

Die Schweiz droht ihre führende Rolle in Bildung, Forschung und Innovation zu verlieren. Deshalb braucht es nachhaltige Investitionen und keine…

11. September 2023 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Der Ökonom Mathias Binswanger verortet «Bullshit-Forschung» in der Psychologie. Doch die Ellen, mit denen er misst, lassen die…

24. August 2023 | Anik Stark

Ärzt*innen setzen mehr und mehr Tests zur Früherkennung von Krankheiten ein, doch wie aussagekräftig sind sie? Anhand eines Beispiels aus dem Artikel…

20. August 2023 | Dominik Scherrer

In dieser Episode sprechen wir mit Stefano Amberg über das sogenannte Essential Use Concept und wie es auf Mikroplastik angewendet werden kann. Wir…

22. Juli 2023 | Eva Maria Hodel , Nicola Low , Annika Frahsa , Selina Wegmüller

Die nächste Pandemie könnte schon morgen ausbrechen, und wir wissen nicht, welcher Erreger sie auslösen wird. Wie können wir uns auf diese Situation…

13. Juli 2023 | Lara Thurnherr

Der Einfluss von Künstlicher Intelligenz auf unsere Gesellschaft wächst stetig, doch die Regulierung hinkt derzeit den technologischen Entwicklungen…

5. Juli 2023 | Rahel Schmidt

Vergewaltigungen sind auch in der Schweiz ein massives Problem – die Rede ist von rund 400’000 potentiell Betroffenen. Leider ist die Betreuung von…

29. Juni 2023 | Xulia Maillot Rodriguez

Wie oft hörst du das Wort "Gluten" in deinem Alltag? Das Wort ist in Magazinen, Zeitungen, Geschäften zu finden. Prominente und Spitzensportler*innen…

28. Juni 2023 | Sabine Stadler

Aujourd’hui, en Suisse, les personnes de 65 ans ou plus sont plus nombreuses que les jeunes entre 0 et 19 ans. Le vieillissement de la population…

21. Juni 2023 | Mykola Makhortykh , Aleksandra Urman , Maryna Sydorova

AI-driven systems have the power to influence political decisions. Well-informed citizens are fundamental to direct democracy in Switzerland, but the…

14. Juni 2023 | Corinne Othenin-Girard

Im Jahr 2018 hat der chinesische Forscher Dr. He Jiankui die ersten CRIPRS-Genom-editierten Babys hervorgebracht. Diese Technik wirft viele ethische…

9. Juni 2023 | Victor Schmid

Die Wissenschaft verhält sich bei relevanten gesellschaftlichen Krisensituationen nicht rechtzeitig situationsgerecht und kommunikativ richtig. Sie…

6. Juni 2023 | Guido Baldi , Monica Jeggli

Eine heftige Debatte ist entstanden um die Teilzeitarbeit. Guido Baldi und Monica Jeggli versuchen eine Einordnung. Sie kommen zum Schluss: Die…

4. Juni 2023 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Frauen schätzen sich durchschnittlich etwas linker ein als Männer, hat jüngst eine Auswertung gezeigt. Dennoch ist es übertrieben, von einem «Graben»…

31. Mai 2023 | Rahel Schmidt , Jan Isler

Am Reatch Ideenwettbewerb 2022 gewonnen und nun vom Franxini Innovation Hub unterstützt: Rahel Schmidt und ihr Team handeln

31. Mai 2023 | Rahel Schmidt , Jan Isler

Am Reatch Ideenwettbewerb 2022 gewonnen und nun vom Franxini Innovation Hub unterstützt: Rahel Schmidt und ihr Team handeln

24. Mai 2023 | Sabrina Burkhard

Hitzewellen werden bei fortschreitendem Klimawandel häufiger, intensiver und länger. Die Hitze führt vor allem bei der älteren Bevölkerung zu…

20. Mai 2023 | Anne Jomard

Most people know they should eat enough protein, but might not be able to explain why that is. In the first article of our Future of Protein series,…

13. Mai 2023 | Sarah Scheidmantel

Seit einer Woche hagelt es Kritik für einen Artikel der Sonntagszeitung. Doch die Gretchenfrage bleibt unbeantwortet: Wie lassen sich…

8. Mai 2023 | Eva Maria Hodel , Nicola Low

The next pandemic of an infectious disease could start tomorrow. The involvement of communities in research that is relevant to their lives is our…

2. Mai 2023 | Maximilian Spitz

Der russische Angriffskrieg in der Ukraine stellt die Neutralität der Schweiz vor grosse Herausforderungen. Die Schweiz ist in dieser Frage…

24. April 2023 | Stefano Amberg

Neben Plastikmüll befindet sich auch immer mehr Mikroplastik in unserer Umwelt. Die Gefahren dieser Mikropartikel sind noch weitestgehend unbekannt…

19. April 2023 | Hannah Schoch , Luca Schaufelberger , Alexandra Zingg

Der 3. Studien-Zyklus (Doktorat) ist momentan den universitären Hochschulen (UH) vorbehalten. Fachhochschulen (FH) sind somit auf eine Kooperation…

17. April 2023 | Monica Jeggli

Geopolitische Risiken haben in den vergangenen Jahren laufend zugenommen. Der russische Angriffskrieg gegen die Ukraine oder die Spannungen zwischen…

9. April 2023 | Dominik Scherrer

In dieser Episode haben wir Rahel Schmidt zu Gast, die im Herbst 2022 den Ideenwettbewerb vom Franxini-Projekt von Reatch gewonnen hat. Ihre Idee ist…

4. April 2023 | Lucius Arn

Um die Krisen von morgen zu meistern, brauchen wir als Gesellschaft Vorstellungsvielfalt als Rüstzeug. Dafür notwendig ist ein gemeinsames…

26. März 2023 | Elisabeth Abs

Macht die Schweiz genug, um das 1.5-Grad-Ziel des Pariser Klimaabkommens zu erfüllen und die Klimakatastrophe abzuwenden? Nein, findet die Gruppe…

23. März 2023 | Laura de Smalen

In biomedical research, more attention, funding, and resources are given to diseases that relate to wealthy populations – regardless of the fact that…

6. März 2023 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Forschung und politischer Aktivismus schliessen sich nicht a priori aus, findet Sabine Süsstrunk. Dennoch rät die Präsidentin des Schweizerischen…

24. Februar 2023 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wissenschaft und politischer Aktivismus gehen nicht zusammen, heisst es oft. Aber wieso hört man diese Kritik nur bei jenen, die auf die Strasse…

4. Februar 2023 | Henry Broadbent

Biodiversity, the diversity of living organisms, plays an important role in the evolution and survival of species. However, human activity is causing…

29. Januar 2023 | Guido Baldi

Immer wieder wird argumentiert, dass die Schweizer Wirtschaft vor allem durch die hohe Zuwanderung wachse und beim Wachstum pro Kopf hinter andere…

27. Januar 2023 | Lea Bächlin

Vom Vorspiel auf dem Theater bis zur Vorgeschichte der Ukrainekrise drehte sich bei einer der Sommerakademien der Schweizerischen Studienstiftung…

27. Januar 2023 | Luca Schaufelberger , David Marti

Covid-19 und die Energiekrise haben gezeigt: Die Schweiz tut sich schwer mit Digitalisierung. Bei der künstlichen Intelligenz ist unser Land…

13. Januar 2023 | Luca Schaufelberger , Hannah Schoch , Alexandra Zingg

Für einen effektiven Umgang mit akuten, wie auch graduellen Krisen ist es wichtig, bestehendes Wissen von Forschenden breit abgestützt in politische…

13. Januar 2023 | Manuel Merki

Demokratische Öffentlichkeiten, die faktenbasiert entscheiden wollen, brauchen Wege, um die Faktizität von Informationen schnell und einfach…

12. Januar 2023 | Jankó Weibel

Weisse Kittel wehen hinter gehetzten Schritten durch die Gänge, im Hintergrund übertönen knallende Helikopterrotoren gerade die Sirenen einer…

27. Dezember 2022 | Guido Baldi , Maximilian G. H. Bisges

Receive money without doing anything? While this might sound strange, this is essentially the idea behind helicopter money. While some described…

19. Dezember 2022 | Nicole Müller

Blauer Himmel, graue Berge, grüne Wiesen – ein Wandertag wie aus dem Bilderbuch. Doch bis vor wenigen Jahren war es in den Alpen noch weniger grün.…

12. Dezember 2022 | Simon Scheidegger

Unsere Hirnmasse ist auf den Platz des Schädels beschränkt und so auch unsere Denkkapazität. Brain-Computer-Interfaces (BCI) – Technologien, die…

10. Dezember 2022 | Tim Buser

Im Gegensatz zur Corona-Pandemie werden die Affenpocken in der Schweiz weniger als ge-samtgesellschaftliche Krise wahrgenommen. Dies hat nicht nur…

1. Dezember 2022 | Amélie Garrido

L’utilité ! Maître-mot de la Modernité, loi suprême régissant nos systèmes politiques, économiques, sociaux. Utilité se décline à tous les temps,…

12. November 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Forschende engagieren sich lautstark in politischen Debatten bis hin zu illegalen Sitzblockaden auf Schweizer Autobahnen. Ist das Anmassung oder…

3. November 2022 | Noémie Frezel-Jacob , Adélie Garin

Gibt es einen richtigen Weg, wie sich Forschende in die Politik einbringen können? Um diese Frage zu beantworten, hat Reatch politisch aktive…

25. Oktober 2022 | Noémie Frezel-Jacob

Avec de plus en plus de membres francophones et basés en Romandie, et de plus en plus d'événements, Reatch commence bel et bien à s’implanter à…

19. Oktober 2022 | Anna Stoffel , Laura Neal , Pauliina Rumm , Nicole Geiger , Leif Sieben , Olivia Sieber

Over the past two years, we all had to learn the importance of mental wellbeing the hard way. Many of us have changed our habits and behaviors in our…

5. Oktober 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

«Brücken schlagen zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik.» Dies ist eine der zentralen Empfehlungen des Schweizerischen Wissenschaftsrates SWR im…

21. September 2022 | Anniina Maurer , Florian Zoller

Die Ukraine ist aus ökonomischer Perspektive ein sehr interessantes Land, welches grosses Potenzial aufweist und auch für die Schweiz attraktiv ist.…

21. August 2022 | Tomas Marik

Welche Herausforderungen erwarten junge Generationen und wie lassen sich diese bewältigen? Ein Gespräch mit dem Wirtschaftsprofessor Bernd…

2. August 2022 | David Marti , Luca Schaufelberger

Das Franxini-Projekt von Reatch präsentiert in Kollaboration mit Pour Demain, einem Think-Tank mit KI-Schwerpunkt, einen Vorschlag für ein Monitoring…

5. Juli 2022 |

Welche Erwartungen haben Politik und Wissenschaft aneinander? 2021 hat sich unsere Autorin mit Politiker*innen und Wissenschaftler*innen…

16. Juni 2022 | Tomas Marik

Den umweltschädlichen Konsum zu stoppen und gleichzeitig unseren Lebensstandard in einem wachstumsorientierten System aufrechtzuerhalten, scheint…

7. Juni 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Guido Baldi , Angela Bearth

Im Bericht «Schweiz 2035 – Think Tanks beantworten 20 Zukunftsfragen» werden die grossen Zukunftsfragen für die Schweiz der nächsten 10 bis 15 Jahre…

1. Juni 2022 | Alisha Föry

Die Forschung deutet darauf hin, dass Entzündungsprozesse im Körper Depressionen auslösen. Neueste wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse über diese…

31. Mai 2022 | Hannah Schoch , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Stümperhafte Geisteswissenschaftler*innen sollte sich die Schweiz genauso wenig leisten wie schlechte Pflegeleute. Doch wer die…

23. Mai 2022 | Luca Schaufelberger

Ist Wasserstoff ein wichtiger Energieträger der Zukunft oder nur ein Hype? Wir zeigen auf, welche Vorschläge die nationale Politik aktuell…

18. Mai 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Claudio Paganini

Im wissenschaftlichen Publikationswesen gibt es gravierende Missstände. Doch die Open-Access-Praxis ist nicht das Problem, sondern ein Teil der…

12. Mai 2022 | Noémie Frezel-Jacob , Klara Soukup

Alors que la plupart des mesures sanitaires étaient levées en Suisse depuis presque une semaine, les participant·e·s à l'événement Reaching into the…

29. April 2022 | Dominik Scherrer

Russia has been waging a war in Ukraine since 24 February 2022. In the last 2 months, the news about this war has been inundated, not only in the…

29. April 2022 | Manuel Merki , Servan Luciano Grüninger , Luca Schaufelberger

Die menschgemachte Klimaerwärmung ist real. Wir müssen den Klimawandel bremsen und hierfür unsere Emissionen senken.

13. April 2022 | Anouk Petitpierre

Für das Färben von Bluejeans braucht es jährlich 400 Tonnen des Blutgiftes Anilin. Diese gelangen auf ungenügend geschützte Arbeitende, ins Abwasser…

5. April 2022 | Roger Germann

Künstliche Intelligenz (KI) ist mittlerweile allgegenwärtig. Über das gesellschaftliche Potential und die ethischen Herausforderungen wird bereits…

31. März 2022 | Manuel Merki , Sebastian Behrens

Reatch reicht Antrag auf ein nationales Forschungsprogramm (NFP) ein. Die Ergebenisse sollen als Grundlage zur Digitalisierung der Demokratie dienen.

29. März 2022 | Sonja Leyvraz

Tiefe Preise, ständig neue Kollektionen, schlechte Qualität: Die Fast-Fashion Industrie verursacht horrend hohe soziale und ökologische Kosten, für…

27. März 2022 | Sabrina Kessler , Miriam S. Cano Pardo , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Inzidenz. Positivitätsrate. Reproduktionszahl. Aus der Berichterstattung zur Corona-Pandemie sind Zahlen und Statistiken nicht wegzudenken. Ob die…

22. März 2022 | Selina Widmer

Nikola Kompa erklärt, was die Philosophie zur Sichtweise der Biologie auf die menschliche Sprache beitragen kann und zeigt im Gespräch eindrücklich…

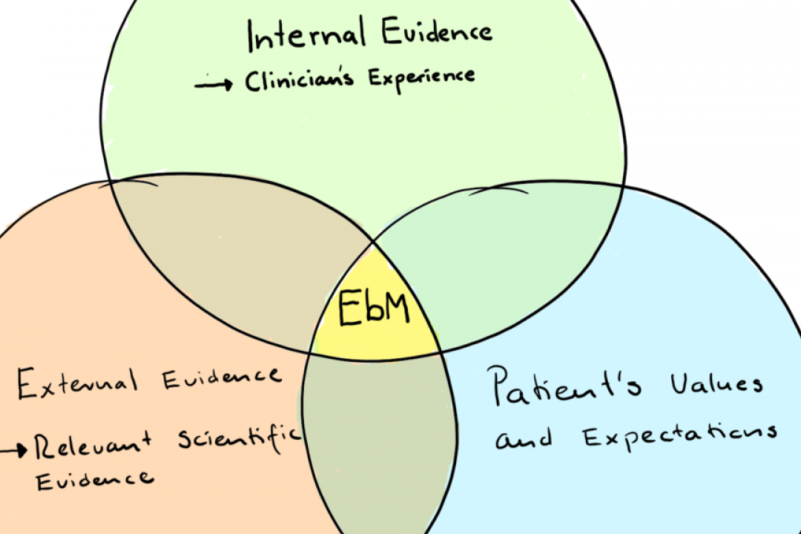

15. März 2022 | Philippe Valmaggia

Im Spital gilt es täglich, Entscheidungen über das Wohlbefinden von Patient:innen zu treffen. Die medizinischen Empfehlungen müssen dabei mit…

20. Februar 2022 | Judith Blage

Die Volksinitiative zum Tierversuchsverbot will Experimente an Tieren für die Forschung

verbieten. Doch ohne Tierversuche kann es keine Durchbrüche…

13. Februar 2022 | Victor Joss

Neurofeedback soll es ermöglichen, sonst verborgene Gehirnfunktionen aktiv zu kontrollieren und damit psychische Krankheiten zu heilen. Doch wie…

11. Februar 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die bisherige Berichterstattung zur Initiative «Ja zum Tier- und Menschenversuchsverbot», über die am 13. Februar 2022 abgestimmt wird, ist krass…

10. Februar 2022 | Marion de Vevey

In many parts of Africa, engaging in homosexual intercourse or being part of the LGBTQ+ community is punishable with imprisonment or even death…

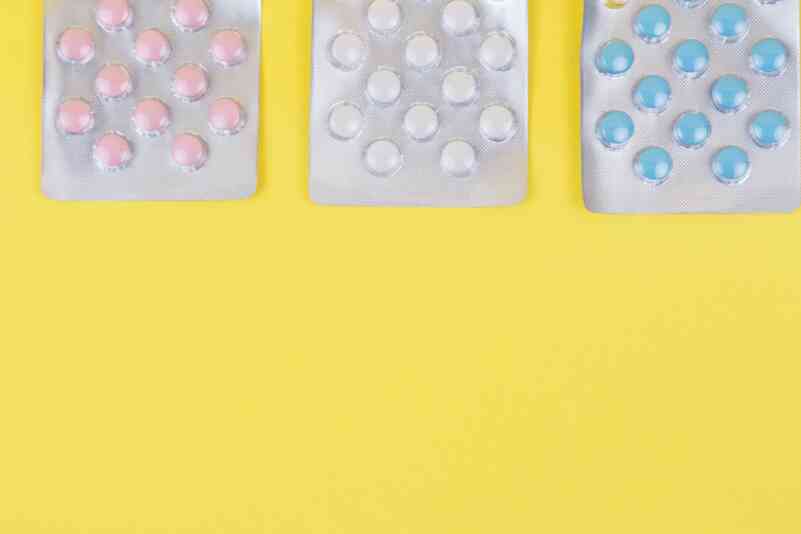

9. Februar 2022 | Michaela Egli

Tierversuche sind in der Arzneimittelentwicklung international verpflichtender Standard. Eine Initiative möchte alle Tierversuche und…

4. Februar 2022 | Nicolas Zahn , Luca Schaufelberger , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wie lässt sich das Zusammenspiel zwischen Politik und Wissenschaften verbessern? Diese Frage diskutierten Vertreter*innen aus Politik und…

3. Februar 2022 | Noémie Frezel-Jacob

Noémie Frezel, de l'équipe nano talks, parle chez Alma & Georges de son engagement pour Reatch et pourquoi elle souhaite un débat informé,…

2. Februar 2022 | Maya Guido , Alexis Perakis , Amir Mikail

Algorithmen sind rege im Einsatz: im Gesundheitswesen, den sozialen Medien, Online-Suchmaschinen und unzähligen weiteren Bereichen. Auch bei der…

1. Februar 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Marie Zufferey

En soumettant à la délibération populaire une initiative aussi extrême, les pourfendeur·euse·s de l’expérimentation animale prennent le risque qu’une…

31. Januar 2022 | Maria Lung

Des joues rouges, une peau pâle, une taille fine : derrière l'idée de la beauté féminine au 18ème siècle se cache une maladie, prisée par les…

19. Januar 2022 | Antonia Straden

Immer häufiger werden stärkere Klimaschutzmassnahmen vor Gericht statt im Parlament verhandelt. Ist es problematisch, wenn Gerichte die CO2-Gesetze…

17. Januar 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Forscher beraten Politiker, ohne sie zu respektieren. Politikerinnen verweisen auf die Wissenschaft, ohne sie zu würdigen. Das ist keine gute…

13. Januar 2022 | Anna Funk

Forschungsfreiheit ist ein wichtiges Gut. Trotzdem wird gerade die biomedizinische Forschung streng reguliert – eine relativ junge Entwicklung. Heute…

11. Januar 2022 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wenn Forschende sich in der öffentlichen Debatte über Tierversuche Gehör verschaffen wollen, braucht es mehr als Fakten. Sie müssen sich auch mit…

5. Januar 2022 | Olivia Meier

Scrollt man sich durch die Liste des UNESCO-Welterbes, kommt Fernweh auf. Einige der schönsten Orte auf der Welt sind dort versammelt. Darunter die…

29. Dezember 2021 | Caroline Hasler

Ob im Supermarkt, in der Freizeit oder in politischen Abstimmungen: Meist haben wir das Gefühl, freie Entscheidungen zu treffen. Aber stimmt das…

1. Dezember 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

In der Schweiz gehen strenge Regulierung und Spitzenforschung Hand in Hand. Einigen ist das nicht genug. Sie wollen ein Totalverbot der…

26. November 2021 | Nadine Felber

Vor einem Jahr gewann die Idee der «Source Engine» von Nadine Felber den Reatch Ideenwettbewerb. In diesem Blog-Artikel zieht sie Bilanz und…

24. November 2021 | Martina von Arx , Levyn Bürki

Das war das Rendez-vous 2021 auf dem Waisenhausplatz in Bern.

Bis bald im Sommer 2023, wenn es wieder heisst zuhören, fragen, diskutieren, staunen…

21. November 2021 | Dominik Scherrer

Am 28. November 2021 stimmen wir in der Schweiz über die sogenannte Pflegeinitiative ab. Bei dieser Initiative und dem Gegenvorschlag geht es darum,…

12. November 2021 | Thore Schönfeldt

Überall wimmelt es von Geschichten vom Untergang der Menschheit. Solche Dystopien hinterlassen tiefe Spuren in unserem Denken. Können sie zur…

4. November 2021 | Angela Odermatt

Alte Krankheitserreger und DNA auf tausendjährigen Skeletten und Mumien zu finden, tönt nach Science Fiction. Und doch ist es Alltag in der…

19. Oktober 2021 | Dominik Scherrer

Werden wir bald von einer künstlichen Intelligenz evaluiert, wenn wir uns auf eine Stelle bewerben? Vom automatisierten CV Screening bis hin zur…

18. Oktober 2021 | Lukas Robers

Das gescheiterte CO2-Gesetz hat marktwirtschaftliche Grundsätze zu wenig berücksichtigt. Ein neuer Vorschlag muss auf Effizienz, internationale…

14. Oktober 2021 | Victor Joss

Die Knotentheorie, eines der aktivsten mathematischen Fachgebiete, entstand im 19. Jahrhundert aus einer gewagten - und völlig falschen - Theorie…

10. Oktober 2021 | Tomas Marik

Ein Interview mit dem Nobelpreisträger für Chemie Prof. Dr. Kurt Wüthrich zum Verhältnis von Politik und Wissenschaft und darüber, wie die Politik…

3. Oktober 2021 | Mariasole Agazzi

With the current situation man plans to colonise the Moon and arrive on Mars with the same internationally recognised laws at his disposal as only…

3. Oktober 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Niemand will unnötige oder unnütze Tierversuche. Doch an der Frage, was nötig und nützlich ist, scheiden sich die Geister.

30. September 2021 | Rahel Schmidt , Luca Schaufelberger

Wer kennt sie nicht, die weissen Globuli? Sie sollen helfen bei Erkältungen, Zahnen und vielen anderen Beschwerden. Obwohl die Wissenschaft der…

22. September 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Servan Grüninger spricht beim Deutschlandfunk über den Unterschied zwischen Meinungen und empirisch belegbaren und theoretisch überzeugenden…

20. September 2021 | Nathalie Gasser , Dominik Scherrer

Wie können Forschende mehr in Kontakt treten mit der Bevölkerung? Und an welchen Themen wird aktuell im Bereich “Geschlecht” geforscht? Das…

10. September 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

There are many ways for academics to engage with policymakers. Here are some rules of thumb which we hope will be useful for your next projects.

7. September 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Geht es um Corona, Klimawandel oder andere wissenschaftliche Themen, beklagen Forschung und Medien vermehrt eine «falsche Ausgewogenheit» (engl.…

7. September 2021 | Caroline Hasler

Beschleicht dich ein ungutes Gefühl, wenn du Fast Food bestellst, obwohl du dir doch vorgenommen hast, dich gesünder zu ernähren? Die Psychologie hat…

3. September 2021 | Carla Kreis

Im Gespräch mit vier Naturwissenschaftler*innen geht Franxini-Projektleiterin Anna Krebs zentralen Fragen auf den Grund: Was erwarten Forschende von…

22. August 2021 | Reatch! Research. Think. Change.

An Evidence Review Group organized by the Swiss Academy of Sciences has looked in a multi-stakeholder scientific dialogue process at the currently…

22. August 2021 | Katrin Schregenberger

Falschinformationen werden oft mit angeblich wissenschaftlichen Belegen untermauert. Wissenschaftsglaube kann so zu einer Falle werden.

6. August 2021 | Chantal Adelmann

Nutzbringende Leistungen aus der Natur werden anhand von Ökosystemleistungen quantifiziert, um Umweltverschmutzung oder die Zerstörung von…

31. Juli 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Although our knowledge of the universe is steadily increasing thanks to the sciences and humanities, verifiable facts, such as the fact that the…

24. Juli 2021 | Luca Schaufelberger

Braucht die Schweiz Kernenergie, um dem Klimawandel entgegenzutreten? So der Vorschlag von Lukas Robers, Doktorand in Nukleartechnik an der ETH…

15. Juli 2021 | Lena Greil

Seit einiger Zeit sorgt ein neues Reatch-Angebot für Aufsehen: das Franxini-Projekt. Was oder vielmehr wer dahinter steckt und wie es weitergeht,…

5. Juli 2021 | Sarah Sermondadaz

Der Sozialpsychologe Pascal Wagner-Egger geht in seinem neuen Buch der Frage nach, wie Verschwörungsvorstellungen verankert und verbreitet werden.…

1. Juli 2021 | Katrin Schregenberger

Verschwörungstheorien packen uns bei unseren Schwächen. Das zeigt der Fall Judy Mikovits.

21. Juni 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Obwohl unser Wissen über das Universum dank den Wissenschaften stetig zunimmt, werden in letzter Zeit überprüfbare Tatsachen, wie zum Beispiel, dass…

9. Juni 2021 | Vinisha Varghese

If you were granted one wish to decide what your future workplace should look like, what would it be? The science of Biomimicry suggests that nature…

31. Mai 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Schweizer Wissenschaftsvermittler wollten herausfinden, wie die Pandemie die Wissenschaftskommunikation beeinflusste. Ihre Umfrage liefert zwar…

18. Mai 2021 | Lukas Robers

Ideenwettbewerb-Teilnehmer Lukas Robers fragt sich, wie wir unsere Energie in Zukunft bereitstellen wollen und fordert statt ideologischer Kämpfe…

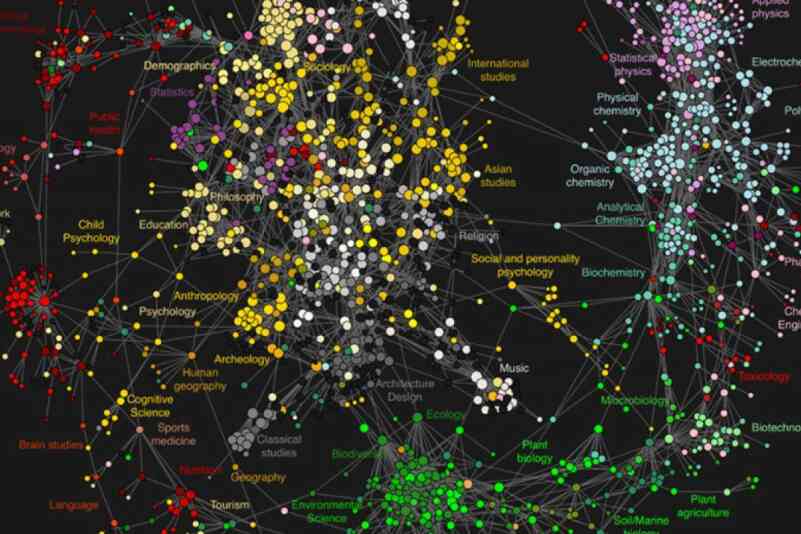

14. Mai 2021 | Lena Greil

The fact that men are more reluctant towards wearing masks than women is only one consequence of toxic masculinity highlighted by the current…

10. Mai 2021 | Sven Nösberger

Ideenwettbewerb-Teilnehmer Sven Nösberger sorgt sich um die direkte Demokratie der Schweiz. Er möchte es deshalb Laien ermöglichen, sich…

6. Mai 2021 | Angela Odermatt , Sina Benesch

«Der Bund fördert die wissenschaftliche Forschung und die Innovation», heisst es in der Bundesverfassung. Tatsächlich fliesst Jahr für Jahr eine…

3. Mai 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Nach den jüngsten Bundesratsentscheiden wird einmal mehr die «wissenschaftliche Ignoranz» der Politik lamentiert. Das entlarvt nicht nur die…

30. April 2021 | Sabrina Kessler , Corinne Schweizer , Silke Fürst , Edda Humprecht

Silke Fürst, Sabrina H. Kessler, Corinne Schweizer und Edda Humprecht vom Institut für Kommunikationswissenschaft und Medienforschung wünschen sich…

23. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Über ein Jahr nach Ausbruch der Pandemie sorgt das politische Spiel mit COVID-19-Kennzahlen weiterhin für Verwirrung, Ärger und Frustration. Dabei…

21. April 2021 | Alexis Perakis , Maya Guido , Amir Mikail

Die wenigen Suchergebnisse rund um das Thema algorithmischer Verzerrungen in der Schweiz sind ernüchternd. Doch leider repräsentieren sie nur zu gut,…

14. April 2021 | Timothy Rabozzi , Christine Kienzle , Lucas Kyriacou , Tanja Mitric

Eine Beschwerde für einen verspäteten Flug per Mausklick einreichen? Rechtsberatung von einem Chatbot bekommen? Oder Dokumente online notariell…

7. April 2021 | Julian Garritzmann

Welche Bildungspolitik wollen Bürger*innen in Europa? Und spielt es für die Politiker*innen überhaupt irgendeine Rolle, was sie wollen? Wir gingen…

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Michaela Egli

Die Natur-, Sozial- und Geisteswissenschaften führen eine Vielzahl von Forschungsprojekten durch, an denen Menschen als Versuchsteilnehmer*innen…

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Michaela Egli

Alle Forschungsprojekte mit Menschen, die unter das Humanforschungsgesetz (HFG) fallen, brauchen eine behördliche Bewilligung. Darunter fällt die…

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Michaela Egli

Wichtige Grundsätze zur Forschung am Menschen sind bereits in der Verfassung festgelegt. Dort ist unter anderem festgehalten, dass eine Teilnahme an…

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Michaela Egli

Jedes Forschungsprojekt, das unter das Humanforschungsgesetz fällt, benötigt eine Bewilligung von einer unabhängigen kantonalen Ethikkommission.…

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler

Ein Forschungsprojekt mit Menschen wird nur dann zugelassen, wenn für die Versuchsteilnehmer*innen kein unzumutbares Risiko besteht und der…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Klinische Studien sind medizinische Forschungsprojekte, bei denen die Versuchsteilnehmer*innen eine bestimmte Behandlung zugewiesen bekommen, um…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Klinische Studien werden von sogenannten «Sponsoren» initiiert. Dabei kann es sich um Einzelpersonen oder Institutionen wie beispielsweise…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

An einer klinischen Studie kann im Prinzip jeder Mensch teilnehmen. Notwendige Voraussetzung dafür ist aber in jedem Fall eine freiwillige Zustimmung…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Die grösste Verantwortung für die Sicherheit der Teilnehmer*innen liegt bei den Forschenden und den Behörden. Doch auch Patient*innen selbst tragen…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Für alle Therapien mit Zulassungserfordernis braucht es in der Schweiz wissenschaftliche Daten, die zeigen, dass die Therapie wirksam, sicher und…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Bevor ein neues Medikament auf den Markt gelangt, muss es nach präklinischen Versuchen erfolgreich drei Phasen von klinischen Versuchen durchlaufen.…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Präklinische und klinische Versuche erkennen die meisten Nebenwirkungen eines neuen Arzneimittels vor seiner Zulassung. Gewisse Nebenwirkungen, die…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Randomisierte, kontrollierte und doppelt verblindete klinische Versuche liefern wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse von besonders hoher Qualität und…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Neben klugen Studiendesigns sorgen vor allem gesetzliche Auflagen sowie nationale und internationale Richtlinien dafür, dass der Einfluss von…

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Bewilligungspflichtige Versuche mit Menschen müssen in der Schweiz bei einer Behörde eingereicht werden werden und ergeben damit eine untere Grenze…

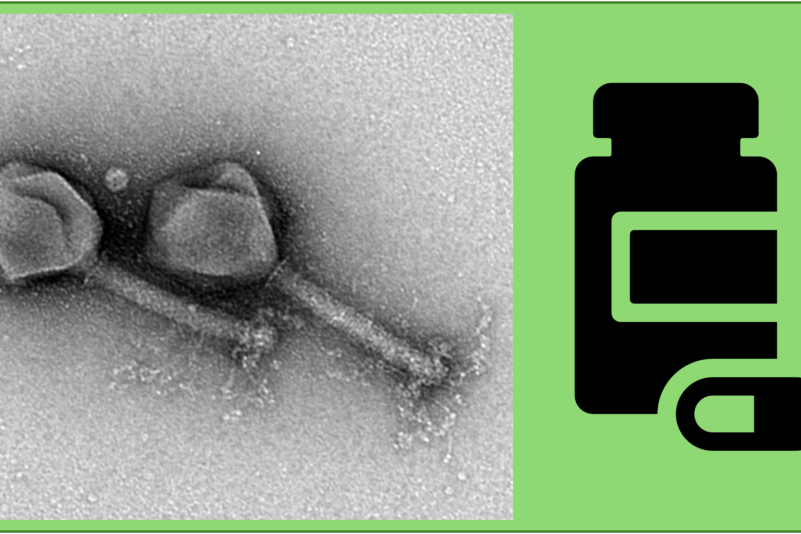

1. April 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Es gibt mehrere Gründe, warum die Entwicklung mehrerer COVID-19 Impfungen vergleichsweise rasant schnell ging. Unter anderem waren einerseits …

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler

Ein Totalverbot der Forschung mit Menschen würde nicht nur zu einem wissenschaftlichen Kahlschlag führen, sondern auch die Sicherheit von…

1. April 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler

Eine Annahme der Initiative würde es verbieten, neue Medikamente, Impfungen oder andere medizinische Produkte in der Schweiz einzusetzen, wenn diese…

27. März 2021 | Lionel Pousaz

Wann soll man falsche Schlagzeilen im Internet korrigieren? Am besten erst nachdem jemand die Falschinformation gelesen hat, wie eine neue Studie…

25. März 2021 | Joel Lüthi , Nicolas Zahn

Wissenschaften und Bildung brauchen eine verlässliche Beziehung mit der EU

17. März 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Angelika Hardegger kritisiert in einem Kommentar unreflektierte Experteneuphorie – doch sie irrt, wenn sie die Schweizer Demokratie als «beste…

4. März 2021 |

Jonas Wittwer argumentiert, dass wir, um zu guten Entscheidungen zu gelangen, hinsichtlich unserer eigenen Fähigkeiten zu Erkenntnis zu gelangen,…

1. März 2021 | Fabio Hasler , Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Ob Medikamententests an Mäusen im Labor, Beobachtungsstudien an Kapuzineraffen in Zoos oder ökologische Untersuchungen von Tieren in der freien…

1. März 2021 | Pascal Broggi

Forschende, die einen Tierversuch durchführen, müssen ein Gesuch ans kantonale Veterinäramt stellen. Diese beurteilt das Gesuch in Zusammenarbeit mit…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Um eine Bewilligung zu erhalten, müssen Forschende eine detaillierte Beschreibung des Versuchsziels und der geplanten Versuche einreichen. Die…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

An tierversuchsfreien Methoden wird aus ethischen, wirtschaftlichen, rechtlichen und auch wissenschaftlichen Überlegungen intensiv geforscht. Für…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Pascal Broggi

Der Einsatz von tierversuchsfreien Methoden wie Zell- und Gewebekulturen, Computersimulationen oder sog. «Organ-Chips» ist Alltag in der…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Pascal Broggi , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Tiere und Menschen sind evolutionär miteinander verwandt, weshalb viele biologische Strukturen und Prozesse miteinander vergleichbar sind. Es gibt…

1. März 2021 | Pascal Broggi

Wenn ein vielversprechendes Medikament nicht auf den Markt kommt, kann das verschiedene Gründe haben:

1. Die Resultate aus der präklinischen…

1. März 2021 | Pascal Broggi , Jonas Füglistaler

Damit Medikamente an Menschen getestet werden dürfen, muss aus ethischen und rechtlichen Gründen die Wirksamkeit und Sicherheit für die Probanden so…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Damit biomedizinische Experimente aussagekräftige Ergebnisse liefern, braucht es eine sorgsame Planung, Durchführung und Analyse von Experimenten.…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Präklinische und klinische Studien können die meisten Nebenwirkungen frühzeitig erkennen. Bei sehr seltenen Nebenwirkungen kann es jedoch vorkommen,…

1. März 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler , Servan Luciano Grüninger

Da Forschungsgelder in der Regel nicht für ein bestimmtes Modell, sondern zum Erforschen einer bestimmten wissenschaftlichen Frage verwendet werden,…

1. März 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Versuchstiere dürfen in der Schweiz höheren Belastungen ausgesetzt werden als Heimtiere, wenn der Erkenntnisgewinn oder der Nutzen für Medizin und…

1. März 2021 | Pascal Broggi , Fabio Hasler

Versuchstiere werden mehrheitlich gezüchtet und müssen aus einer bewilligten Versuchstierhaltung im Inland oder einer gleichwertigen ausländischen…

1. März 2021 | Pascal Broggi , Fabio Hasler

Die meisten Versuchstiere, die belastenden Eingriffen ausgesetzt waren, werden nach dem Abschluss des Versuchs schmerzfrei getötet. Das gilt…

27. Februar 2021 | Joel Lüthi

Eine gute Beziehung braucht Arbeit. Wenn Forschende weiterhin von europäischer Kooperation profitieren wollen, müssen sie sich der Debatte über das…

27. Februar 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse sind entscheidend, um aus der Corona-Krise zu kommen. Maulkörbe und Einschränkungen der wissenschaftlichen Freiheit…

25. Februar 2021 | Lisa Kwasny

Die derzeit oft gesehenen Demonstrationen von sogenannten Coronaleugner*innen kommen mit einer gewissen revolutionären Symbolik daher. Lassen sich…

17. Februar 2021 | Lena Greil

Stereotypes geschlechterspezifisches Verhalten muss nicht zwingend schlecht sein. Möchten wir uns aber von den Geschlechterrollen befreien und…

11. Februar 2021 | Guido Baldi

Am 20. Januar wurde Joe Biden als neuer US-Präsident vereidigt. Zusammen mit Vizepräsidentin Kamala Harris und der ganzen Regierung steht er vor…

11. Februar 2021 | Leonard Creutzburg , Viktoria Cologna

Ideenwettbewerb-Teilnehmer*innen Leonard und Viktoria präsentieren in ihrem Beitrag eine Alternative zum Wirtschaftswachstum: Postwachstum.

6. Februar 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

«Traue keiner Statistik, die du nicht selbst gefälscht hast.» Besser beschreibt kein Bonmot das zynische Misstrauen von vielen, wenn es um…

1. Februar 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Übertragbarkeit, Kosten und Misserfolge: Geht es um Tierversuche, zirkulieren sehr viele verschiedene Zahlen, welche aus dem Zusammenhang gerissen zu…

1. Februar 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Fabio Hasler , Pascal Broggi

Aussagen zu Tierversuchen mit besonderem Fokus auf den Schweizer Kontext und schwerbelastende Versuche.

1. Februar 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Fabio Hasler , Pascal Broggi

Eine Sammlung von Behauptungen zur Übertragbarkeit und Aussagekraft von Tierversuchen.

1. Februar 2021 | Servan Luciano Grüninger , Jonas Füglistaler , Fabio Hasler , Pascal Broggi

Eine Sammlung von Behauptungen über Tierversuche aus Grossbritannien, die auch in Debatten in der Schweiz immer wieder bemüht werden.

27. Januar 2021 | Jonas Füglistaler

Obwohl zu Beginn der COVID-19-Pandemie noch denkbar wenig über das Coronavirus bekannt war, schien das kollektive Ziel vergleichbar einfach: «Flatten…

20. Januar 2021 | Uwe Thümmel , Sandra Volken , Rasmus Ischebeck

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a lot of work has moved online, including academic conferences. Could virtual conferences allow us to continue enjoying…

20. Januar 2021 | Manuel Merki

Angesichts rasanter wissenschaftlicher Entwicklungen entstehen berechtigte Ängste vor deren Auswirkungen auf die Gesellschaft. Als Reaktion darauf…

11. Januar 2021 | Valentina Jordan

Als grösstes Rohstoffhandelszentrum der Welt spielt die Schweiz eine wichtige Rolle im transnationalen Kupferhandel. Welches Verhältnis hat die…

10. Januar 2021 | Nadine Felber

Nadine Felber hat die Lösung gegen Fake-News und Verschwörungstheorien: eine Source Engine. Diese soll Online-Inhalte auf ihre Quelle prüfen und…

10. Januar 2021 | Maria Lung

Il sauvait le vie de Churchill. Pendant longtemps, l’antibiotique a été considéré comme un remède miracle dans la lutte contre les maladies. Mais…

10. Januar 2021 | Christian Roduner

Wieso werden wir durch die Schule nur in unseren kognitiven Kompetenzen systematisch und professionell gefördert?, fragte sich Christian Roduner, der…

10. Januar 2021 | Simon Walo

Die fortschreitende Digitalisierung fordert, dass Arbeitnehmer*innen sich ein Leben lang weiterbilden. Aufgrund mangelhafter Daten ist jedoch unklar,…

16. Dezember 2020 | Dominik Scherrer

Interview mit Nadine Felber über ihre Idee einer “Source Engine”, welche sie beim Reatch Ideenwettbewerb im Oktober 2020 vorgestellt hatte und damit…

9. Dezember 2020 | Anina Steinlin

Der Mensch sieht sich gerne als Opfer der Digitalisierung – und glaubt, er sei modernen Technologien etwa auf dem Arbeitsmarkt schutzlos…

30. November 2020 | Katrin Schregenberger

Die Vergangenheit der Schweizer Landschaft ist aussergewöhnlich gut erforscht. Pollen verraten, was Menschen in der Jungsteinzeit anbauten. Das…

17. November 2020 | Franziska Ehrler

Das Wohlbefinden der Schweizer Bevölkerung blieb auch während des Lockdowns im Frühjahr hoch. Dies liegt möglicherweise auch daran, dass in der…

11. November 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Niederländische Forschende haben bei 67 Tierversuchsprojekten untersucht, wie häufig die daraus entstehenden Ergebnisse veröffentlicht worden sind.…

6. November 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Was ist dran an der Behauptung, dass wir nur einen Bruchteil unseres Gehirns nutzen? Nicht viel: Unser Gehirn ist nämlich viel zu teuer, als dass wir…

1. November 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Hätte die Politik auf die wissenschaftlichen Einschätzungen gehört, würden wir nicht im Corona-Schlamassel stecken, kritisieren Mitglieder der…

26. Oktober 2020 | Carole Imhof

Densifier les surfaces habitables tout en mettant à profit les services rendus par le sol urbain représente un défi rarement relevé par les villes.…

23. Oktober 2020 | Dominik Scherrer

Den Wissenschafts-Thinktank Reatch gibt es nun schon weit über fünf Jahre. Servan Grüninger, der Präsident und Mitgründer von Reatch, stellt sich den…

19. Oktober 2020 | Fabio Keller

Das Parlament ist zu langsam, deshalb muss der Bundesrat manchmal tun, was er eben tun muss. Bekäme der demokratische Prozess ein Update, wäre…

11. Oktober 2020 | Elfie Suter

Seit Beginn der Corona-Pandemie kursieren auf Social Media verschiedene Verschwörungstheorien über den Ursprung des Virus. Doch wie verbreiten sich…

8. Oktober 2020 | Olivia Meier

Wie war das nochmal: Benutzen wir nur 10% unseres Hirns? Enthält Spinat tatsächlich viel Eisen? Und schadet Lesen unter der Decke wirklich den Augen?…

2. Oktober 2020 | Alina Hunkeler , Gian Giacomo Ruschetti

Bezieht man sich auf diverse Ratgeber im Internet, ist Kreativität eine der Eigenschaften, die Arbeitgeber*innen vermehrt bei ihrer Personalauswahl…

25. September 2020 | Alina Hunkeler , Gian Giacomo Ruschetti

Der Übertritt in den Ruhestand ist für ältere Menschen zunehmend mit Unsicherheiten verbunden. Einsamkeit im Alter und Altersarmut sind…

24. September 2020 | Katrin Schregenberger

Wer gegen Klimaschutzmassnahmen ist und über grosse Wirtschaftsmacht verfügt, hat gute Karten, in öffentlichen Debatten zu Wort zu kommen. Zumindest…

16. September 2020 | Philippe Gaspoz

Gefühle, Schwächen, Verletzlichkeit: alles nichts für einen wirklichen Mann, oder? Wie dieses Verständnis von Männlichkeit die Gesundheit von Männern…

10. September 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

«Auch mit Statistiken lässt sich trefflich lügen» schreibt Milosz Matuschek in seinem Kommentar zu den Corona-Massnahmen - und erbringt den Tatbeweis…

7. September 2020 | Janik Mutter

Auch schon auf Fake News hereingefallen? Empfehlungen könnten dazu beitragen, Falschnachrichten in Zukunft zu entdecken.

6. September 2020 | Dominik Scherrer

Das “Scimpact” Programm bietet dir die Chance, mit deinem Wissen und deinem Einsatz etwas in der Gesellschaft zu bewirken. Darum melde dich an. Wir…

25. August 2020 | Lara Gafner

Warnende Wissenschaft, ignorante Politik – in Zeiten der Klimakrise weckt die Serie «Chernobyl» aktuelle Assoziationen. Doch was können wir daraus…

20. August 2020 | Martina Burger

Ein Kulturwissenschaftler schreibt über die Klimaerwärmung. Wie kommt ein Fachfremder dazu, sich eines so komplexen Themas anzunehmen? Im Interview…

20. August 2020 | Olivia Meier

Komplexe Themen so zu vermitteln, dass alle sie verstehen, ist eine Kunst. Genau mit dieser Aufgabe werden Leute, die Wissenschaftskommunikation…

6. August 2020 | Friederike Vinzenz

Das Bundesamt für Statistik verschafft mehr Klarheit in Sachen Nachhaltigkeit mit dem Indikatorensystem MONET 2030. Ist die Schweiz bei der…

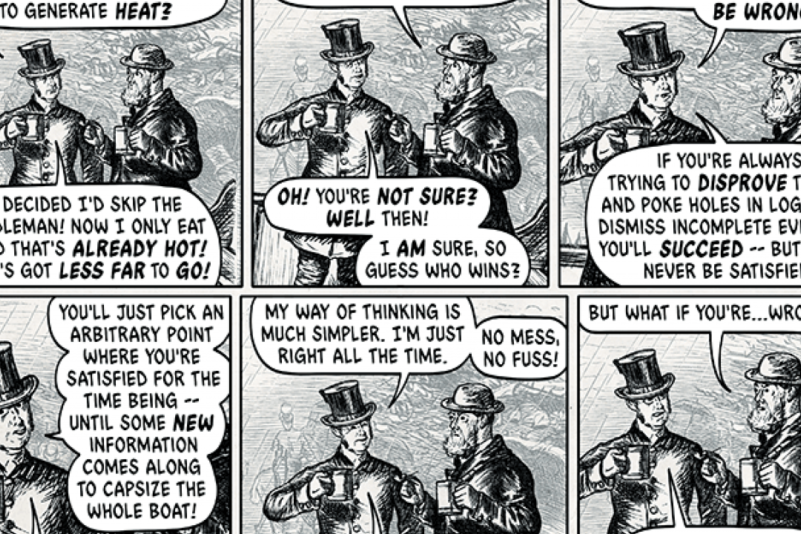

1. August 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wenn die Wissenschaft Weltbilder bedroht, sind ihre Leugner schnell zur Stelle. Ein Überblick über beliebte rhetorische Tricks und…

31. Juli 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Der Philosoph und Theologe Markus Huppenbauer engagierte sich seit mehreren Jahren im Beirat von reatch und förderte die Ideenschmiede mit…

15. Juni 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Seit Computer ganze Texte verfassen, Bilder fälschen und die menschliche Sprache verstehen können, sind «künstliche neuronale Netze» in aller Munde.…

12. Juni 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Das Kartenspiel «Swiss Development Geek» testet Faktenwissen zu Nachhaltigkeit und Entwicklung – und zeigt, wie oft wir falschen Vorstellungen von…

6. Juni 2020 | Olivia Meier

Von den einen als dringliches Mittel zur gesellschaftlichen Veränderung gefordert, von den anderen als ästhetischer Totalschaden verhasst.…

2. Juni 2020 | Sandro Bucher

Wie wir über das Coronavirus denken und was wir darüber wissen, beeinflusst neben Politikern auch Wissenschaftler und Medienschaffende. Was es dabei…

29. Mai 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Unrealistische Vorstellungen in unseren Köpfen verhindern beim Klimaschutz den Blick aufs Ganze.

25. Mai 2020 | Guido Baldi , Kaja Meier , Tanja Mitric , Timothy Rabozzi

Immer mehr Menschen wünschen sich eine Flexibilisierung der Arbeitsformen und Arbeitszeiten, denn das Arbeitsrecht hinkt der Realität zu oft…

13. Mai 2020 | Olivia Meier

Es gibt nicht nur das biologische, sondern auch das soziale Geschlecht – darin ist man sich in der Geschlechterforschung relativ einig. Wie es zu…

11. Mai 2020 |

Jonas Wittwer berichtet, wie er als Doktorand am Philosophischen Institut der Universität Bern die letzten turbulenten Wochen erlebt hat und was das…

2. Mai 2020 | Olivia Meier

Laut Statistiken sind Depressionen bei Frauen häufiger als bei Männern. Dafür sind die Suizid-Zahlen bei Männern deutlich höher. Die Gründe dafür…

27. April 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die Initiative «Ja zum Tier- und Menschenversuchsverbot» würde künftig in der Schweiz lebensrettende Medikamente verbieten. Das sollte man klar und…

23. April 2020 | Katrin Schregenberger

Die Corona-Epidemie hat Forschende in die öffentliche Debatte katapultiert. Doch wie lange halten sie sich?

22. April 2020 | Sören Mohrdieck

With global carbon dioxide emissions on the rise, it is imperative that we provide economic incentives for reduction. Why carbon pricing is an…

20. April 2020 | Anouk Petitpierre

Warum gehört eine Hand zu meinem Körper, eine Handprothese nicht? Ein Diskussionsbericht über die schwierige Suche nach einer überzeugenden Antwort.

14. April 2020 | Jonas Füglistaler

Obwohl viele Medien (z.B. Republik, NZZ, Tages-Anzeiger) erstaunlich gut und differenziert über die aktuelle Notlage berichten, fehlen oft…

5. April 2020 | Johannes Hahn

Im vergangenen Jahr jagte ein klimapolitischer Entscheid den nächsten. Trotzdem drohen die Klimaziele weitgehend verfehlt zu werden. Was auf den…

1. April 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Eine (etwas vollständigere) Orientierungshilfe, worauf es beim Vergleich von (COVID-19)-Statistiken zu achten gilt. Bonus: Warum wir auch mit…

30. März 2020 |

Die Philosophen Eric Schliesser und Eric Winsberger erläutern wichtige Unterschiede zwischen der Klimaforschung und der Forschung zu Covid-19. Jonas…

27. März 2020 | Luc Schnell

Forschende lassen in Experimenten Roboter auf die gleichen Illusionen hereinfallen wie Menschen. Ihre Resultate gewähren tiefe Einblicke ins…

23. März 2020 | Guido Baldi

Zurzeit erledigt ein Grossteil der Bevölkerung seine Arbeit von zu Hause aus. Wie verändert das Home Office unsere Arbeit? Expert*innen sprechen in…

23. März 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

In den Medien und den sozialen Netzwerken sind Zahlen zu COVID-19 allgegenwärtig. Eine (unvollständige) Orientierungshilfe, worauf es beim Vergleich…

21. März 2020 | Stefan Gugler

Die Schweiz muss so schnell wie möglich das Testen von Verdachtsfällen als Kernkomponente der Kontrolle von COVID-19 verstärken – das fordern mehrere…

20. März 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Um über ein komplexes Thema wie die Covid-19-Pandemie berichten zu können, wenden sich Medien gerne an Experten - oder an jene, die sich dafür…

19. März 2020 | Hilda Bastian

Der Mediziner John Ioannidis kritisiert, dass wir bezüglich Covid-19 Entscheide träfen, ohne zuverlässige Daten zu haben. Doch die Schlüsse, die er…

18. März 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die Ereignisse um Covid-19 überschlagen sich, die Lage ist ernst. Immer mehr Forschende melden sich mit Einschätzungen und Empfehlungen in den Medien…

13. März 2020 |

Ein Artikel in der Basler Zeitung vom 13. März 2020

13. März 2020 | Danny Bürkli

Wie vier Erklärungsansätze aus der Systemtheorie uns dabei helfen können, die Coronavirus-Epidemie zu verstehen.

10. März 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wenn Politiker nach Statistiken rufen, ist Vorsicht geboten. Meist haben sie nämlich klare Vorstellungen davon, was das Ergebnis sein darf und was…

3. März 2020 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die politischen Debatten über 5G, Klimawandel und Tierversuche zeigen: Immer wieder verlieren sich Medien bei wissenschaftlichen und technischen…

28. Februar 2020 | Andreas Stoller

Mittels Virtual-Reality-Brillen werden Menschen zur Körpertausch-Illusion verleitet. Für einen Moment glauben sie, im Körper eines Fremden zu…

15. Februar 2020 | Anuschka Arni

Welches Produkt soll ich kaufen, IP-Suisse oder Naturaplan? Und wofür steht eigentlich der nordische Schwan? Eine kleine Hilfestellung für den Umgang…

7. Februar 2020 | Elina Herrendorf

Klassische Berufsmusikerinnen stehen unter enormem Druck und müssen stets Spitzenleistungen abliefern. Das führt häufig zu psychischem Stress oder…

17. Januar 2020 | Andreea Ciuprina

2019 is over but not the flu season. A good time to have a closer look at the virus causing this nasty respiratory infection and how to fight it.

13. Dezember 2019 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Eine Initiative bläst zum Frontalangriff auf Forschung und Medizin. Doch wer das Kind mit dem Badewasser ausschüttet, sollte sich über nasse Füsse…

1. Dezember 2019 | Nicolà Bezzola

Neue Managementkonzepte versprechen den Mitarbeitenden oft viel: Autonomie, Selbstverwirklichung und Sinnhaftigkeit. Doch die Realität sieht häufig…

17. November 2019 | Guido Baldi , Martina Pons

The labor share of income, that is, the proportion of national income that is paid to labor, has been declining in many advanced economies.…

9. November 2019 | Uwe Thümmel

«Roboter und Software können ein Viertel aller Jobs übernehmen», titelte die NZZ. Was steckt hinter solchen Zahlen?

6. November 2019 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Die Schweiz zeigt, wie sich Spitzenforschung und strenger Tierschutz vereinen lassen. Auf den Lorbeeren ausruhen dürfen sich Schweizer Forschende…

30. Oktober 2019 | Nicolà Bezzola

Auf tsri.ch vom 30. Oktober 2019.

24. Oktober 2019 |

Auf Radio SRF 1 «Forum» vom 24. Oktober 2019.

19. Oktober 2019 | Alina Hunkeler , Gian Giacomo Ruschetti

Auf tsri.ch vom 19. Oktober 2019.

15. Oktober 2019 | Remo Agovic , Guido Baldi

Keine Massenarbeitslosigkeit, sondern Jobpolarisierung und individualisierte Lebensumstände. Wie der technologische Wandel unsere Arbeitswelt…

10. Oktober 2019 | Guido Baldi , Remo Agovic

Auf tsri.ch vom 10. Oktober 2019.

7. Oktober 2019 | Philipp Emch

Virtuelle Objekte, Räume und Welten halten in unseren Alltag Einzug. Handelt es sich dabei um reale Objekte oder soziale Konstrukte? Philipp Emch…

3. Oktober 2019 | Guido Baldi , Uwe Thümmel

«Wenn Roboter unsere Jobs übernehmen, dann sollten sie auch Steuern zahlen», sagte Bill Gates in einem Video, dass 2017 die Runde machte. Klingt…

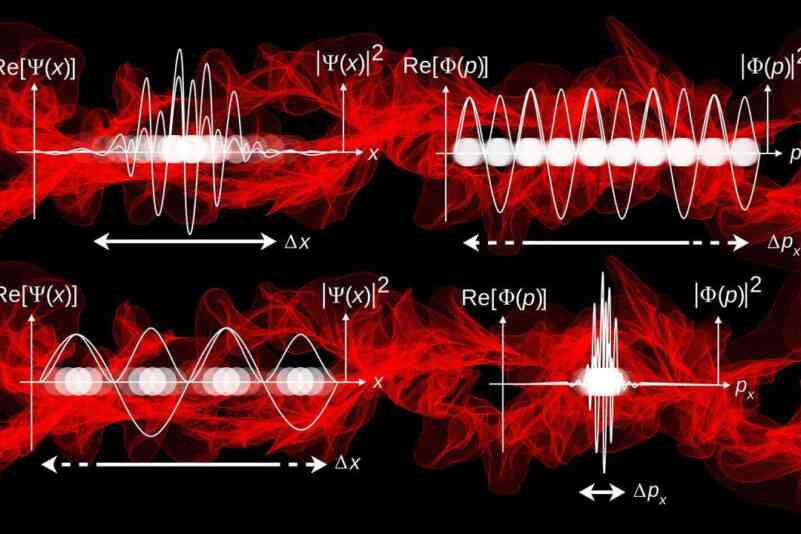

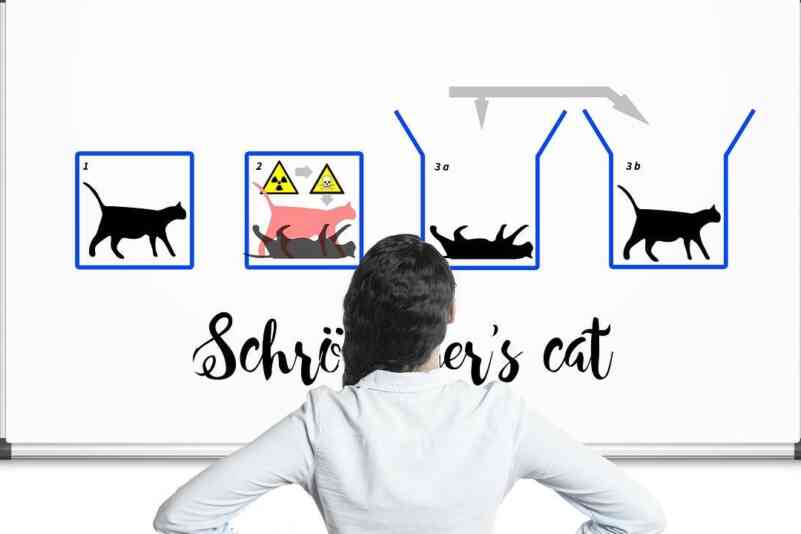

20. September 2019 | Johannes Fankhauser

Die moderne Physik hat es geschafft, Theorien hervorzubringen, ohne genau zu wissen, wovon sie handeln. In der wohl erfolgreichsten Theorie der…

13. September 2019 | Matthias Gröbner

Die physikalische Beschreibung der Welt lässt sich nicht mit unserer Intuition in Verbindung bringen. Welches Bild kann uns die Physik dann über die…

2. September 2019 |

Aus dem UZH News vom 02. September 2019.

9. August 2019 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Geht es um Imagepflege und politische Durchschlagskraft, kann den Schweizer Bauern niemand das Wasser reichen. Höchste Zeit für die Wissenschaft, von…

2. August 2019 | Guido Baldi , Frédéric Kluser

Die Löhne in vielen Volkswirtschaften legen nur verhalten zu. Demgegenüber sind die Gewinne einiger grosser Firmen kräftig gestiegen. Was ist dran am…

24. Juli 2019 |

Wenn es um Geschlechtersternchen oder das Binnen-I geht, mischen sich viele Expert*innen in die Debatte ein. Dabei sind sie aber nicht nur inhaltlich…

5. Juli 2019 | Lukas Robers

Wer in der Klimafrage nur mit Wirtschaftlichkeit argumentiert, verkennt die Dringlichkeit des Problems. Nicht nur Photovoltaik, sondern auch die…

24. Mai 2019 |

Aus dem Blick vom 24. Mai 2019.

13. Mai 2019 | Anna Suppa

Energiesparen liegt im Trend. Die Energiepolitik setzt vor allem auf Eigenverantwortung. Ganz nach dem Motto: «Das Verhalten jedes Einzelnen…

1. Mai 2019 |

Die schweizerische Antwort auf den weltweiten March for Science am 4. Mai wird eine Dialog-Veranstaltung am 6./7. September in Bern sein. Organisiert…

30. April 2019 | Marie Louise Schubert

Weshalb Physikerinnen und Physiker in mehr Disziplinen ausgebildet werden müssen, als nur in Physik und Mathematik.

20. April 2019 | Olivia Meier

Hört man das Wort «Rechenzentrum», hat man meist ein Gebäude voller schwarzer Kästen mit vielen farbigen Kabeln im Kopf. Doch wie sieht die Welt der…

17. April 2019 | Nicolà Bezzola

Over the recent decades changing labour regimes have increased income and employment uncertainty for many people. Radical ideas to address these…

26. Februar 2019 |

Wie man wirkungsvoll das Vertrauen in die Wissenschaften schwächt, konnte man dieser Tage anhand der Diskussion um die Stickoxid-Grenzwerte in…

19. Februar 2019 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wer den wissenschaftlichen Konsens anzweifelt, muss das mit wissenschaftlichen, nicht mit politischen Argumenten tun.

8. Januar 2019 | Rafael Eggli

Die Quantenphysik ist die Grundlage zahlreicher Schlüsseltechnologien der Moderne und hat unser Bild von der Welt grundlegend verändert. Für…

22. Dezember 2018 | Jannes Jegminat

Wie zu viele Köche den Eintopf verderben und welche verschiedenen Meinungsträger und Wahrnehmungen bezüglich künstlicher Intelligenz (KI) existieren.

14. Dezember 2018 | Jonas Schmid

Die Digitalisierung revolutioniert unseren Alltag. Und beeinflusst, was wir von der Welt sehen. Über die damit verbundenen Risiken und den Umgang…

6. Dezember 2018 | Anna Knörr

Heutzutage lebt man zweimal – in der Realität und in der Digitalität. Diese neue Welt entsteht vor unseren Augen, doch die Datenmengen, auf denen sie…

1. Dezember 2018 | Bettina Zimmermann

Die mutmasslich genetisch veränderten Zwillinge aus China rücken die ethischen Herausforderungen der Gentechnologie ins Rampenlicht. Diese ethischen…

28. November 2018 | Olivia Meier

Wir fürchten uns vor Geheimdiensten, die unsere Daten sammeln, Hackern, die unsere E-Mails lesen und davor, dass unsere Kreditkarteninformationen in…

8. November 2018 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

In den Medien kommen immer die gleichen Forschenden zu Wort. Die Wissenschaften tragen daran eine Mitschuld, doch auch die Medien stehen in der…

17. Oktober 2018 | Lisa Kistler

Fortschritt ist mehr als Medikamente und Start-Ups. Denn Forschung strebt nicht allein nach Innovation, sondern ist vor allem die Suche nach…

27. September 2018 | Constantin David Kilcher

Die Geschichte ist voll von unerwarteten Ereignissen. Erst der scharfe Blick der Historikerin offenbart das Wahrscheinliche im Unerwarteten.

20. September 2018 | Matthias Roesti

You can’t polish a turd. Or so we thought. By publishing influential papers based on questionable data, some economists showed otherwise. But in the…

13. September 2018 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Akademische Forschende konkurrieren in erster Linie um Anerkennung. Wissenschaftlich gewinnbringend ist das nur bedingt. Denn das Wettrennen um die…

2. September 2018 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Politische Entscheide machen vor universitären Toren keinen Halt. Warum sich auch Forschende aufs Politikparkett wagen sollten.

12. August 2018 | Nicolas Zahn

Will die Schweiz die Chancen der Digitalisierung nutzen, müssen die Wissenschaften eine stärkere Rolle in politischen Diskussionen spielen. Aber wie?

28. Juli 2018 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Wissenschaftler werfen dem Europäischen Gerichtshof vor, vor Lobbyisten eingeknickt zu sein. Diese Polemik ist irreführend, denn nicht die Richter,…

20. Juli 2018 | Andreea Ciuprina

A new form of prenatal genetic testing has revolutionized prenatal care: Noninvasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT). Initially developed to detect…

4. Juli 2018 |

On Saturday 10th December 2016, Ben Feringa became the fourth Dutchman to receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for ‘the design and synthesis of…

8. Juni 2018 | Tim van Dijk

Openness and transparency are considered to be core values of science. Why, then, do we not yet have an open and transparent culture within science…

5. Juni 2018 |

Aus dem Schweizer Forschungsmagazin «Horizonte» vom 5. Juni 2018.

30. Mai 2018 |

Auf Radio SRF Kultur vom 30. Mai 2018.

18. Mai 2018 | Servan Luciano Grüninger

Gerade bei komplexen Vorlagen müssen Experten deutlich zwischen technischen und politischen Fragen unterscheiden. Sonst blockieren sie die Debatte,…