On June 27th in Lausanne microbiome researcher Prof. Camille Goemans and scientific illustrator Maeva Arnold set out to change that. During an event titled “Pizza, Illustration Scientifique et Microbiote Intestinal” organised by Reatch, they invited participants to explore this hidden universe through a combination of science and art.

The Gut Microbiome: A Myriad of Functions

The focus of the evening was the gut microbiome—the vast ecosystem of microbes living in our intestines. Far from being passive passengers, these organisms help break down complex fibers, produce essential vitamins like B and K, support immune function by teaching the body what to attack or tolerate, and manufacture neurotransmitters that influence how we feel and think.

One of the most intriguing areas of research is the gut–brain axis, the two-way communication system between our digestive tract and our central nervous system. For instance, inflammation in the gut can alter mood, and stress can in turn influence gut health—highlighting the deep interconnection between body and mind. Scientists are only beginning to unravel the vast and complex roles the gut microbiome plays in human physiology and health.

Diet: The Microbiome’s Main Course

Unlike some other body systems, the microbiome responds rapidly to what we eat. Fiber-rich foods—vegetables, fruits, whole grains—serve as fuel for beneficial bacteria, while fermented foods like yogurt, kimchi, and sauerkraut introduce live microbes that can boost diversity and resilience.

In contrast, a diet high in processed foods, sugars, and unhealthy fats can promote dysbiosis, an imbalance in the microbial community. Dysbiosis has been linked to a wide range of conditions including allergies, obesity, autoimmune diseases, depression, type 2 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and certain cancers. However, scientists caution that while correlations are strong, proving cause and effect is challenging. Current evidence suggests that for obesity and IBD, the causal links are more firmly established; for other diseases, research is ongoing.

One striking theme from the discussion was how much we still don’t know. Despite an explosion of research, there is no single, universal definition of what a “healthy microbiome” looks like. As highlighted in a key review by the Human Microbiome Project, microbiome health might be better defined by ecological stability, functional resilience, and metabolic capability, rather than a fixed list of “good” microbes.

Microbiome composition varies widely between individuals—shaped by genetics, age, geography, and lifestyle—and even across different body sites. Beyond the gut, we have rich microbial ecosystems in the skin, mouth, respiratory tract, and vaginal environment, each with its own role in health. Expanding research to understand these diverse microbiomes, and how they interact, is an exciting frontier.

Antibiotics: A Double-Edged Sword

The conversation also turned to antibiotics—powerful and often essential drugs that, unfortunately, don't discriminate between harmful and helpful bacteria. While antibiotics treat bacterial infections, they can also wipe out beneficial microbes in the gut. Overuse or misuse may lead to long-term imbalances, increasing the risk of further infections, such as Clostridioides difficile. This bacterium can cause a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, most notably diarrhea, abdominal cramping, fever, and in severe cases, life-threatening inflammation of the colon or kidney failure. These infections are particularly common in healthcare settings and often occur after a course of antibiotics has disrupted the normal gut flora, allowing the bacteria to proliferate. This highlights the importance of responsible antibiotic use to protect both human and microbial health or even contributing to antibiotic resistance.

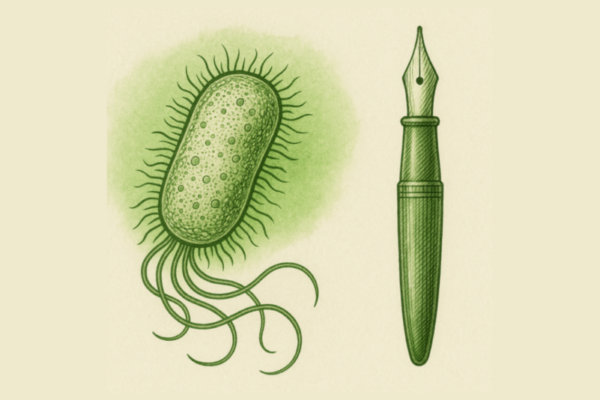

Seeing the Invisible Through Art

After science came art. Under the guidance of Maeva Arnold, participants picked up pencils and began drawing their own interpretations of the gut microbiome—imagining bacteria as colorful characters, crafting tiny worlds on paper. This act of visualizing something that can’t be seen with the naked eye made complex science tangible.

Humor, storytelling, and visual metaphor are powerful tools in science communication: a playful drawing can make an idea stick in memory far longer than a technical chart or dense journal article. As Prof. Goemans noted, bridging art and science invites people to not only understand research but to connect with it on a personal level.

By combining science with creativity, the event reminded us that understanding health isn't just about data—it’s also about curiosity, connection, and storytelling.

Why This Matters

Every meal, every medication, every daily choice sends a signal to our microbial partners—helping them thrive or making life harder for them.

Microbiome science is still young, but it’s moving fast. The more we understand about these hidden ecosystems, the better we can protect them—and ourselves. communities that live within you. They are not just passengers on your life’s journey—they are partners.

And while this event focused on the gut, it’s only one chapter in a much larger story. Our skin, mouth, lungs, and reproductive tract also host unique microbial ecosystems, each playing a role in health and disease. Even beyond our bodies, microbes shape the soil that grows our food and the oceans that regulate our climate. By understanding—and caring for—these diverse microbiomes, we’re not just learning about microbes. We’re learning about the delicate web of life that connects our health to the health of our planet. And that, perhaps, is the most powerful art of all.

And maybe the most important of messages - that science doesn’t exist in isolation: translating research into something people can relate to and act on requires interdisciplinary collaboration between researchers, clinicians, patients, and communicators. And events like this open a window into urgent scientific topics through new and engaging formats.

By combining science with art, we not only make the invisible visible, but also transform knowledge into experience with the ultimate goal of recent scientific discoveries accessible to everyone which merge rigorous science with creative expression, are essential for sparking that understanding. So next time you enjoy a fiber-rich meal or think twice before taking antibiotics, remember the invisible.

References:

Bäckhed, F., Fraser, C. M., Ringel, Y., Sanders, M. E., Sartor, R. B., Sherman, P. M., Versalovic, J., Young, V., & Finlay, B. B. (2012). Defining a healthy human gut microbiome: current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host & Microbe, 12(5), 611–622. PubMed" class="redactor-autoparser-object">https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom...

Gibson, G. R., Hutkins, R., Sanders, M. E., Prescott, S. L., Reimer, R. A., Salminen, S. J., Scott, K., Stanton, C., Swanson, K. S., Cani, P. D., Verbeke, K., & Reid, G. (2021). The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 80(4), 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665121002834

Leveraging diet to engineer the gut microbiome (Perspective). (2021). Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 18(12), 885–902. Luxembourg Institute of Health" class="redactor-autoparser-object">https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575...

O’Keefe, S. J., et al. (2020). Diet and the human gut microbiome: an international review. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. CoLab" class="redactor-autoparser-object">https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620...

Zhang, L., Tuoliken, H., Li, J. et al. Diet, gut microbiota, and health: a review. Food Sci Biotechnol 34, 2087–2099 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-024-01759-x

Appleton, J. (2018). The gut–brain axis: Influence of microbiota on mood and mental health. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, 17(4), 28–32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6469458/

Riehl, J., Wang, J., Schoen, A. M., & Sarkisyan, G. (2023). The importance of the gut microbiome and its signals for a healthy nervous system. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1302957. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2023.1302957/full

Yeoh, Y. K., Chen, Z., Wong, M. C. S., Ho, W. C. S., Chin, M. L., Ng, S. C., … Chan, P. K. S. (2019). Impact of inter‑ and intra‑individual variation, sample storage and sampling fraction on human stool microbial community profiles. PeerJ, 7, e6172. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6172

Scholz, M., Lo, C., & Segre, J. A. (2014). Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Research, 24(10), 1638–1645.

Je, Y., et al. (2022). Causal effect of visceral adipose tissue accumulation on inflammatory bowel disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis (ECCO–JCC). Advance online publication. Oxford Academic" class="redactor-autoparser-object">https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-j...

S.R. Mansour M.A.A. Moustafa, B.M. Saad, R. Hamed, A.-R.A. Moustafa (2025). Impact of diet on human gut microbiome and disease risk. Trends in Gastroenterology & Hepatology. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2052297521000093 ScienceDirect

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (n.d.). The microbiome. Retrieved from https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/microbiome/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Harvard Health Publishing. (n.d.). Understanding the gut microbiome. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-gut-microbiome

Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Antibiotics and gut health. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/expert-answers/antibiotics-and-gut-health/faq-20422350

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Gut microbiome. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/25201-gut-microbiome?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Die Beiträge auf dem Reatch-Blog geben die persönliche Meinung der Autor*innen wieder und entsprechen nicht zwingend derjenigen von Reatch oder seiner Mitglieder.

Comments (0)