This article was written as part of the Reatch programme Scimpact.

A PhD student working on wild animals spent about two years in a remote research camp in an African country in order to collect data. They were forced to hide their homosexuality considering the strict rules of this country and agreed to share their difficult experiences in order to help future researchers and raise awareness. Because of the high risks involved, they wished to remain anonymous. The name of the country is also hidden in order to avoid any repercussions on research activities.

A problem from an early stage

When did your sexual orientation start impacting your PhD experience?

I was completing my master’s degree when I saw the advertisement for the PhD I am doing now. The topic was exactly what I wanted to do. However, when I saw that the data collection would be in Africa, I thought given my sexual orientation, I would not be suited for the position. I felt confident about myself, but not about my own capacity to cope with the potential risk and stress considering the policy against LGBTQ+ people. Therefore, I decided not to apply for the job. A few months passed by and I got in contact with the professor supervising the PhD for a field assistant position. He offered me this PhD instead, which I considered more carefully this time. After many discussions with my loved ones and especially my partner, I applied for it and that is how I started my PhD.

Was your sexual orientation at this stage already something that made you nervous?

Yes, on many aspects. Firstly, for my own safety: I wasn't feeling safe going to this country because of the risks of being sent to jail or being victimized. After discussing the matter with my partner, I felt more confident. On top of this, I was also wondering: "Should I mention my sexual orientation to my supervisor? Should he know the risks involved in sending me to this country? Was the responsibility of taking those risks only mine, or also his?" It felt like I needed to tell him, but equally I did not want to. Firstly, because it is personal, and secondly, because I was worried about discrimination. I was afraid this professor would not want to take the risk of bringing a gay person to the field.

By the time I went to the interview, I took the decision not to disclose my sexual orientation. That was a decision that I had to live with for two years before I came out to my supervisor. However, it was always present in the back of my mind. Since I did not disclose it to him, I could not disclose it to anyone else. I knew that when the time would come for us to have this conversation, I had to make sure he would not worry about me being in the field.

How did this experience of withholding the truth about your sexual orientation affect you psychologically?

When I withheld the information and did not tell anyone about my sexual orientation, it meant that I had to go back into the closet. This was quite horrible. LGBTQ+ people have to come out several times in their lives. That is always very demanding but being finally true to yourself is freeing. You decide not to care anymore, and you accept yourself as you are. However, to take the opposite direction of coming out and going back into the closet is very challenging. By being gay, you are used to oppression from others. Going back in the closet is self-oppression, which is all the more difficult.

Living in constant fear in the field

Then came the time you went to the field. What did you decide to do?

Complete secrecy about my sexual orientation: to them, I was straight. I know some people invented a life and chose to say they had a partner from the opposite sex. I did not, I pretended I was single. I had had a partner for nine years then and it would have been difficult for me to invent a new life: I would have had to provide proof about my pretended partner. Inventing such a massive lie sounded too difficult and unfair to my actual partner.

What would have happened if you had told them you were gay?

It depends on where you say that. In big cities, you might end up in jail. Some people think that if you are a "Mzungu" [Swahili word for a white western person], you are safe, but this is not true. I am aware of a gay man from the US who was detained for three months while I was there. Of course, if you come from a western country that supports LGBTQ+ rights, it is likely that you will eventually be released and sent back to your home country through diplomatic negotiations. However, in the more remote villages, where I am working, there is something called "mob justice", which consists of people executing justice themselves. I personally heard threats that you would not even be arrested: people would stone you to death in the middle of the village.

You worked with local field assistants for a long time. Considering the culture in which they grew up, I guess you could not risk to disclose your sexual orientation to them. How was this experience for you?

I worked for months and even years with the same people, so I have built some bonds and friendships with them. But what sort of friendship? In the back of my mind, I always knew that no matter how close we got, it would be biased by the fact that I was not truthful and that they did not know the real me. I worked with one person specifically, eight hours a day every day, so we built a strong relationship, but I cannot say we were friends, because if he knew the real me, he would have hated me for sure and I prefer not to know what else.

Did you experience any explicit stressful events related to your sexual orientation?

One day, in a bookstore in the capital city, someone I did not know approached me and asked me very bluntly if I was gay. I knew that in some parts of Africa, people from the government would investigate as undercover police officers and arrest gay people to "purge the country". I completely freaked out and wondered if that was the case. What should I say? I knew I had to deny, so I did, but obviously I was very uncomfortable and very aware of my reaction. He asked me whether I would tell him if I was. Again, I freaked out: what should I say that would not raise any suspicion? I couldn’t say no, so I said yes. He asked me whether I was fine with gay people. I replied that I was but that I just was not one of them. He then insinuated that he was gay. At this point, I tried to make casual conversation to hide the fact that I was extremely uncomfortable, and then quickly left. From then on I was convinced that the police were suspicious of me, so I was very nervous going into immigration office the next day to renew my visa. I was afraid I would not get out of there, that the police would arrest me because of that encounter.

«Colleagues are not educated on this issue»

You were staying in a research camp with other people who were not from Africa. How did they handle your sexual orientation?

I have met different international researchers who were open to LGBTQ+ issues. At first, I did not want to share my sexual orientation with them because I wanted to keep control over this information. After feeling pressured to talk about my personal life, I came out to them and mentioned my partner. After that, I came out regularly to new international colleagues, also because I was sick of not being true to myself. However, the more you come out, the more you lose control over the spread of the information. Colleagues are not educated on this issue: they don't perceive the risk as real or big enough. I lost control of this information and was outed to other people. This is a prime example of the need to educate everyone, especially those who are not aware of this issue.

Another problem was their behaviour in the field. Some colleagues would disregard me being uncomfortable, for example when they talked about my partner using the pronoun of the same sex than me. Another example is two European female colleagues fake kissing each other in front of local colleagues because they wanted to challenge their opinion about this issue. They thought it was the right thing to do. Local people got mad and they said that if they did that in the village, they would be stoned to death. That was something I definitely did not want to hear.

Since you’ve come back to Europe, have you still had to be vigilant?

Yes, because I may always go back to the field. Upon coming home, I started a conversation with my supervisor about this issue and the need for more information, education and solutions. I wanted my story to be public, but I had to be careful not to have my name associated with it, because it could be a risk when I go back. For example, colleagues from different parts of Africa follow me on Twitter, so I cannot raise awareness about LGBTQ+ issues in the field there because they would automatically assume that I am part of this community. This is exactly the reason why this interview is anonymous: I cannot let the public know that I am gay.

How did your experience in Africa impact your mental health?

I was constantly stressed, and sometimes afraid. Whenever I was leaving the campsite, I would always fear that I would get arrested when driving. I would fear that a police officer would stop the car and look through my phone and find some texts I had exchanged with my partner. I know it is irrational in a way, but it was always there. Also, when I came out to colleagues in the field, I felt isolated as I quickly realized that people underestimated the risks. It brought me comfort in the sense that I could be myself with them, but I still felt isolated because I was the only one dealing with the risks. Witnessing their careless behaviour made me feel vulnerable.

A real need to protect researchers in the field

Why is it important for you to share your experience?

I don't want anyone to go through what I had to go through. When I started talking about those issues around me, I realized that I was not the only one, and that some people felt even worse about it. I have been trying to raise awareness about these issues in my little research community for a year now, but it is difficult. Indeed, the ones that are directly concerned are already aware of these difficulties, but the hard part is reaching people who do not even think about the risks of being gay in the field. If the overall goal is to avoid these situations, the priority would be to raise this issue with researchers who do not consider it to be one.

How could we make the experience of future researchers better?

This should be a conversation from the very beginning of the entire process, starting at the publication of the job offer. Applicants should know that there is specific support in place in case they need it, at least at university level. There are people who have started to do things, which is good, but it should be more ambitious. It should involve the scientific community worldwide.

What could be implemented?

Many things. Each university could have a diversity and inclusivity office specialised in these issues, with an entire team working on fieldwork. This is manifold: going to African countries is very different from going to New Guinea or Australia. And of course, being LGBTQ+ does not only include being gay but also being transgender, non-binary or queer people, … and people with handicaps, women, people of colour also face their own chanllenges. It goes way beyond LGBTQ+ issues. The scientific community should also discuss and develop appropriate risk assessments (such as how to behave respectfully in the field or how to support LGBTQ+ people). I don't pretend to have all the solutions, but having people actually looking into it would be a good start.

References

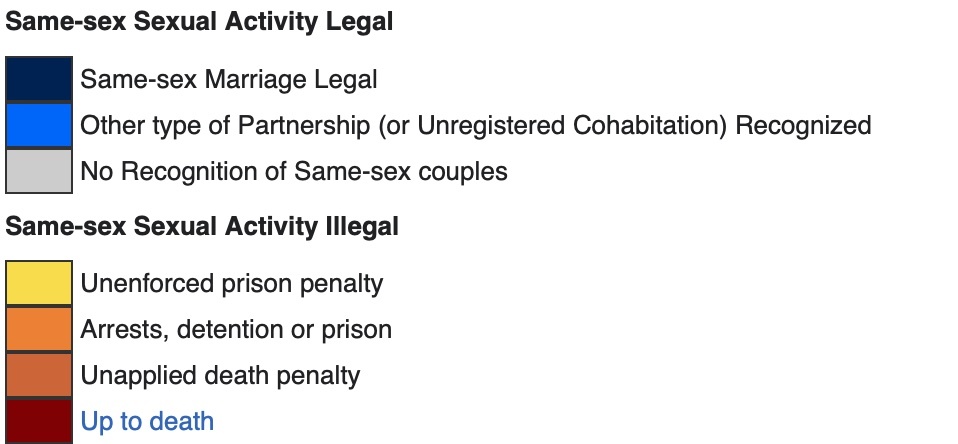

Wikipedia: LGBT rights in Africa, accessed 29.01.22, https://commons.wikimedia.org/....

Wikimedia Commons: African homosexuality laws, version 13 March 2021, accessed 31.01.22, https://commons.wikimedia.org/....

Articles on the Reatch blog reflect the personal opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Reatch or its members.

Comments (0)