When was the last time you bought a banana? Presuming you enjoy bananas, but not enough to grow your own, you probably got them from your local grocery. More likely than not, you chose the banana with the small blue label: you chose the “fairtrade” banana and you probably pay more than you would for a non-fairtrade banana. You do so because you value the fact that this banana was produced more sustainably and equitably than its cheaper competitors. To use the economist’s lingo, you “priced in” the moral virtue of the banana.

As consumers we increasingly value these ethical considerations in our purchasing behavior and, at the very least, we demand that this information is provided to us in a reliable and credible way. We expect to be able to make informed decisions. When it comes to questions of psychological safety or mental wellbeing however, we are often forced to make uninformed decisions. Maybe knowing how exploitative your bank is of its junior analysts would convince you of changing to a competitor. Perhaps as a CEO you would prefer hiring a consulting firm that treats its employees well. At the very least, you would probably care a lot about this type of information when considering your next employer or even university.

When the only way to distinguish the bananas in the groceries was by their color and length, it did not matter how fairly (or more likely, unfairly) they were produced. We solved this by labeling those bananas which were produced with social and financial equity in mind, allowing consumers to make an informed decision. Our society today is suffering from something akin to a “mental wellbeing pandemic”. Why not take the same approach here and establish a label for mental wellbeing? A label for organizations which do better in terms of mental wellbeing than others will not single-handedly solve this crisis but it will allow us to make more informed decisions.

Some Fundamentals

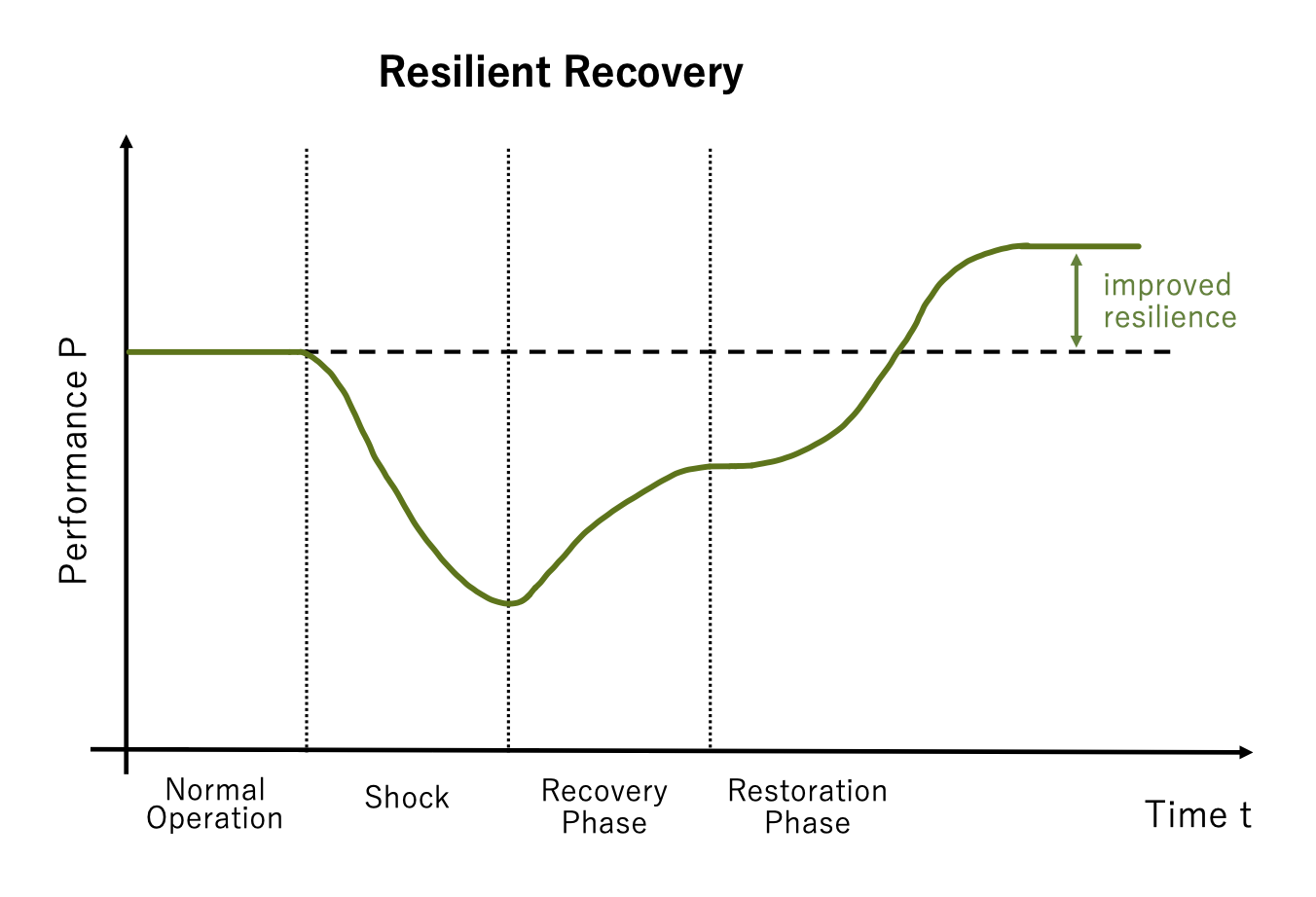

Mental wellbeing, psychological safety, and similar concepts are notoriously difficult to define and to measure. Before a sensible discussion of these issues is possible, we must agree on a conceptualization of the problem. Rather than considering mental wellbeing in its broadest possible sense, we propose focusing on what we call “mental resilience”, i.e. the ability of an individual or a group to recover after a shock to their mental or psychological wellbeing. This definition purposely excludes psychopathology, i.e. states of mental illness, and rather concentrates on the importance of continuous, positive responses to various stressors. This sequence of stress and recovery is well described in other fields and we would like to particularly emphasize the idea of “coming back stronger” after a crisis, see Figure 1.

Not only do we limit our scope to organizations but further to groups, rather than individuals, within these organizations. The type of mental resilience relevant here is fundamentally one of a social nature and we see mental resilience as part of a broader organizational resilience that includes diverse factors such as supply-chain reliability as well as sustainability. Organizations are typically already structured by groups or “teams”. Think of a team as your innermost circle of peers: a department in a big company or a research group in a university for example. Not only does mental resilience depend mostly on our immediate peers, the group often determines how well individuals within it can cope with problems that arise. A team with understanding and supportive members who trust each other will allow any individual to recover stronger from a crisis than in a team with competing or outright antagonistic members.

Furthermore, we posit that mental resilience should always be on the increase. Any team and any organization will constantly be faced with a great number of stressors of varying intensity. These stressors range from a new member joining the team to people refusing to work with each other due to personal disagreement. What distinguishes successful teams from others is not that they experience fewer or less intensive crises but how they deal with them once they arise. A successful team will deal with these problems swiftly and meaningfully, allowing them to recover to a stronger state than before, for example resulting in more trust among the team. Thus, ideally, mental resilience is always increasing over time.

3B - A label for Mental Resilience

This is why we propose a label for organizations with exceptional mental resilience: “3B - Bounce Back Better”. Our independent, non-profit group would measure the mental resilience of all types of organizations to produce both an internal ranking among the different teams within the organization as well as an organization-wide score that would determine the label. The internal ranking would not be published but could enable the organization to learn from successful teams and potentially apply this new knowledge elsewhere. The label itself, however, would become public information accessible to future customers or employees and could also be used by the organization in marketing.

As is commonplace in assessing organizational culture, we would use a survey to assess the mental resilience in individual teams in quantitative terms. Our survey measures mental resilience based on the three key criteria “trust”,” performance”, and “cooperation”. The criterion “trust” considers psychological safety, the authenticity of team leaders, and the autonomy of team members. The criterion "cooperation" deals with team spirit and emotional attachment to the group. “Performance” evaluates to what extent the team contributes to the personal development and the maximum use of one's own potential.

An organization that opts to be evaluated by our label would undergo an intense “launch-phase” in which a baseline measurement is derived through surveying all teams of the organization. These surveys yield a number of points between 1 and 10 for every team. The actual score will then be based on shorter follow-up questionnaires in regular intervals in line with our idea of an ever increasing mental resilience. Following this premise, the ranking itself is not based on one score but rather the largest positive change in points over time. Example questions might include:

Is individual responsibility demanded and encouraged in the team?

Are employees supported in their personal development?

Do team members share the values that are lived within the team?

This form of time-resolved measurement has two major advantages: Firstly, it corrects for the arbitrary scale used in allocating points. The points that individual team-members give on their survey are typically not comparable. One team-member might answer “5/10” to a given question even though they are actually doing a lot better in terms of mental resilience than a colleague who answered “9/10”. Measuring the change in their answers over time, corrects for divergent interpretations of the scale due to personal, cultural, or other reasons. Secondly, measuring the change in mental resilience avoids punishing teams that start from a low base-line in mental resilience or overly rewarding those that had a high score to begin with. This is particularly relevant in organizations with small team-sizes, where statistical outliers are more relevant. Furthermore, we would weigh a team’s score by how much it deviates from the average. A team that has exceptionally high mental resilience in an organization with medium to low mental resilience on average, will therefore contribute much less to the final score than teams that are more reflective of the general situation across the data-set. This also further adjusts for teams with exceptionally high or low mental resilience due to small team-sizes.

The final organization-wide score between 0 to 100 points would thus reward organizations with good mental resilience across its various subdivisions and not those who only focus on the few. Just like the teams themselves, organizations get measured on how much they improve over time. This methodology risks ranking teams or organizations with low mental resilience that can more easily make progress over teams that have already high baseline scores to begin with. We feel however that natural challenges and disruptions will always be part of any team or organization. Even high performers will thus need to constantly adapt and renegotiate their mental resilience over time which is reflected in the survey and the way points are appropriated generally. From a broader point of view, it also incentivizes constant innovation and improvement within organizations and teams, which would hopefully be a big part of the positive impact such a label would have.

The Big Picture

There are multiple potential applications for such a label: As already alluded to, this is certainly relevant for anyone deciding their next employer. It might also change consumer behavior in certain sectors that suffer from particularly bad mental resilience, e.g. consulting or financial services, much like a fairtrade label or Parker score have done for consumers in the supermarket. Ultimately, making an organization’s mental resilience more visible would certainly lead to a strong incentivization to improve on these scores, hopefully resulting in a positive “battle to the top”, where organizations are further motivated by their competitors to improve mental resilience. More to this point, our score would allow us to publish an annual ranking of the top organizations in mental resilience by sectors. This aides in incentivizing organizations to improve in mental resilience as well as drawing valuable public attention to the issue of mental resilience more broadly. The internal ranking of teams could in turn be relevant even to sport clubs who by definition are organized in different teams. In any sport, teams inevitably rely on good mental resilience among their members to succeed and it would thus make sense for a club to assess them on this metric.

Our score could also potentially be included in university rankings, such as QS or Times Higher Education, which are often important factors in the decision of future students. Through this, anyone can gain insight into the mental resilience of a university and how it handles and increases the mental resilience of its students and faculty. The score could even be used in assembling and choosing Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs). ETFs are a type of pooled passive investment that are both low-cost and easy to use, which make them appealing to younger investors. Ethical andin particular sustainable trading has seen a big surge over the last few years. It only seems sensible to extend consumers’ choice to mental wellbeing as well. Why not develop investment options that explicitly focus on mentally resilient organizations similar to funds that focus on green investment.

In any case, bringing mental resilience into the open through a label will increase our focus on these issues and the resources we deploy to them. By rewarding organizations with good mental resilience, their competitors are inherently incentivized to do better too. This holds true for organizations as diverse as companies, sport clubs, and institutions of education and will hopefully be broadly beneficial both to consumers and to employees. If nothing else, the next time you decide on your future employer, business-partner, or university, perhaps you will take just as much time and care as you do in the grocery store deciding on which banana to buy.

References

Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

Liang, F., & Cao, L. (2021). Linking Employee Resilience with Organizational Resilience: The Roles of Coping Mechanism and Managerial Resilience. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, Volume 14, 1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s318632

Comments (0)